As COVID-19 has surged around the globe, the only things matching its pace have been countless new laws and regulations being enacted to control it. Laws can’t stop a virus; but they can be used to curb and control citizens from spreading it. Which jurisdictions have taken effective action and how many lives or dollars justify severe legal restrictions?

What works best in controlling the coronavirus?

Lockdowns? School closures? Travel bans? Restricting public gatherings? Curfews, perhaps?

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the great catastrophe of our age, a public health crisis that has claimed more than 773,000 lives. It has also been one of the greatest experiments in governance ever undertaken, a worldwide petri dish where more than 150 countries have implemented a variety of legal measures aimed at controlling the spread of the virus.

There have been few hard rules. The pandemic playbooks that exist are more than 100 years old, or they apply to relatively localised outbreaks in East Asia. None are suited to the hyper-connected world in which we now live. Not since the Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918 has a virus as deadly as COVID-19 washed through the metropolises of the world, infecting millions and immobilising economics.

Coordination has been limited. Globalisation, it has been observed, has screeched to a grinding halt, leaving countries to go it alone, sealing their borders and grounding their citizens.

Even within a country’s own borders responses have varied greatly, often jarring against each other and creating points of friction between states.

Australian legal responses

In Australia, federal-state cooperation has been aided by the National Cabinet, although Australia’s real advantage has been its size: there are just eight state and territories to corral and a strong tradition of coordination.

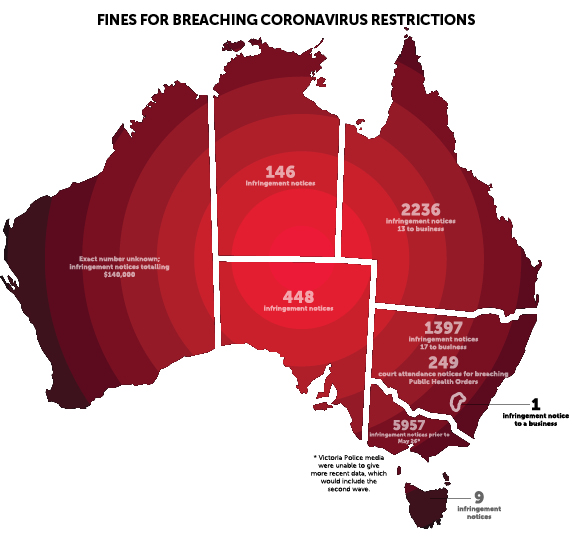

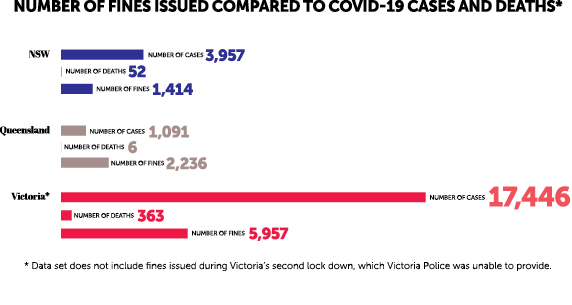

The main instrument of enforcement has been public health notices issued by state and territory health departments and enforced by police. This has led to a maze of restrictions and prohibitions that have varied hugely from state to state. Oddly – perhaps troublingly – there appears to be little correlation between policing and COVID infections across the three eastern states at the forefront of Australia’s epidemic.

In NSW, which until Victoria’s second wave struck was the epicentre of the country’s coronavirus outbreak, police have issued a total of 1,397 infringement notices to individuals and 17 to businesses. Some 249 court attendance notices have been issued over alleged failures to comply with the Public Health Act.

In Queensland, the numbers have been even higher even though the Sunshine state has recorded just 1,091 cases of COVID-19 compared to 3,957 in NSW. A spokesman for Queensland Police told LSJ a total of 2,236 infringement notices had been issued by police, only 13 of which went to businesses. The vast majority of the notices related to various social distancing breaches, although 23 arose from people allegedly lying to police about their whereabouts as they crossed the state’s border.

However, in Victoria, nearly 6,000 fines were reportedly issued prior to the state’s second wave.

According to a report in The Age on 26 May, Victorian Police had issued 5,957 infringement notices. Victoria Police Media were unable to say how many infringement notices had been issued in total since the pandemic began. The updated total is likely to be much higher following the second lockdown: in just one day on 30 July, Victorian Police issued 124 fines to Victorians for not wearing masks, gathering in public, and not abiding by social distancing regulations.

Monique Hurley, a senior lawyer at the Human Rights Law Centre, found a report by the Victorian government into the state’s COVID-19 outbreak revealed that three of the state’s most disadvantaged communities were hit with 10 per cent of all infringements.

“We think that raises concerns about whether communities are being policed fairly and equally,’’ Hurley tells LSJ.

“Historically, when police powers are increased, it is disadvantaged and marginalised groups that are hit the hardest, particularly when there’s broader police discretion that opens the way for racialised policing.’’

International responses

In countries where coordination is weak or non-existent, the results have been disastrous. The United States has recorded more than 5.5 million COVID-19 infections and 170,000 deaths. Nevertheless, six months into the pandemic and some truths have become evident.

Oxford University’s Blavatnick School of Government has undertaken what appears to be the largest study tracking the various policy responses of countries and comparing them to death rates. Using seven commonly applied measures, such as school closures and travel bans, the university’s team of researchers devised the so-called “Stringency Index’’, a metric aimed at gauging the toughness of a country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The index measures stringency on a scale of 1-100 and correlates it with COVID-19 deaths, considered a more reliable measure of severity than infection numbers, which can be skewed by testing rates.

“We do see that higher stringency is associated with a lower death rate,’’ Oxford University lecturer in public policy Anna Petherick tells LSJ. “The more stringent the measure, the more you’d think infections are averted.’’

The Stringency Index is poor news for those arguing for a libertarian approach to COVID. Doing little, as Sweden has famously shown, appears to increase the death rate while providing little extra support for the economy. Sweden’s economy shrank less than the EU average but is roughly on a par with other Nordic countries.

But beyond imposing a tough set of conditions on people, it is difficult to tease out which measures have proved effective. Most COVID-19 policies were introduced quickly and in short succession, making it difficult to isolate their efficacy.

In all cases, though, the point has been to limit people’s movements.

If people are not going to work, doing the shopping or drinking in bars, they are not spreading the disease. Epidemiological studies of COVID have therefore tended to focus on mobility as an indicator of success, usually measured by mobile phone metadata or Google analytics.

Petherick cites one measure she says has been shown to be consistently effective in limiting people’s physical movements.

“What we see in all of these places is that closing workplaces seems to have a pretty consistent effect on mobility. But a lot of these policies are brought in very short succession and together, so there’s a little bit of wariness in teasing out individual polices.’’

Petherick says the longer such policies are in effect, the less useful they become. People begin to chaff against the rules, reverting to old forms of behaviour, although she is careful to note that at no point does mobility revert to “baseline behaviours”.

“We see an erosion in how people’s mobility is affected,’’ she explains. “In the beginning, it reduces a lot, but the longer the policies are in place the less effective they are in constraining mobility.’’

Professor of economics at the University of New South Wales business school Richard Holden tells LSJ this was another argument against the minimalist approach to disease control. He says even when governments declined to impose strict measures constraining people’s movements, mobility declined anyway. Hard-hitting lockdowns imposed during the early stage of a pandemic therefore made for a good financial investment.

“Sweden has had dramatically worse public health outcomes and they have slightly worse economic outcomes compared to other Nordic countries, but slightly better than the European average,’’ Professor Holden says.

“Why? Because there’s been a big reduction in economic activity because they don’t want to get sick. You may as well go all the way for a short period of time rather than go most of the way for a really, really long time.”

Lessons from NZ

New Zealand was among the first movers in the coronavirus.

Leveraging its island status, its relative isolation and the low rate of disease in the general community (New Zealand had just 283 recorded cases), the country went into Stage 4 lockdown in March. Kiwis could travel to the shops, pharmacies and hospitals, but little else. New Zealand’s bold response saw it emerge as the poster child for public health crisis management.

“It was a highly effective and highly admirable approach,’’ University of New South Wales epidemiologist Professor Marylouise McLaws tells LSJ. “As an outbreak epidemiologist I believe all honour should be given to them. Whoever was advising their leader had really expert outbreak understanding.’’

But while New Zealand has shown how effective early action can be, it has also demonstrated the resilience of the virus itself. Five months after New Zealanders shut their country down, Kiwis are in the midst of a second wave. As of 17 August, New Zealand was managing 78 active cases of COVID-19, 58 of which had occurred via community transmission. In response to the climbing numbers, Prime Minster Jacinda Ardern has deferred the country’s general election for a month.

The New Zealand response shows both the efficacy and the limitations of stringency in the face of the disease. While they have been undeniably effective, shut downs are blunt instruments.

If, as some including the World Health Organization have warned, we may be forced to live with the coronavirus, it is hard to see how rolling lockdowns can be a part of a return to economic normality.

The way forward

University of Newcastle public health physician and epidemiologist Dr Craig Dalton says the most effective way of containing a virus as contagious as COVID-19 is rapid testing and contact tracing.

He explains how east Asian countries like South Korea and Hong Kong had learnt the lessons from previous pandemics like SARS and MERS, lessons the rest of the world was largely spared as the viruses petered out.

Dalton says in the early phases of the pandemic, South Korea’s contact tracers had interviewed and isolated known contacts of COVID-19 patients within 24 hours of being diagnosed with the disease.

“Obviously when the case is notified, they may have peaked their infectiousness and transmitted it,’’ Dalton tells LSJ. “So it’s all about the contacts at that point. The time in getting that test down and isolating those contacts is critical. If you can isolate them before they become infectious, that’s fantastic.’’

The US, by contrast, has a notoriously slowly testing regimen and no contact tracing to speak of. Even now, at the height of the pandemic, it can take up to two weeks for people in the US to get their test results, a delay that renders contact tracing wholly worthless. The measure that really counts is time.

“The speed at which an intervention is applied may be just as important as the intervention,’’ Dalton says.

Petherick says Oxford researchers found that a week-long delay in enacting policy measures to a stringency level of 40 led to a death rate 1.7 times higher.

Professor Holden agrees, noting viruses are never static; they are either shrinking or growing.

“You go from a relatively small number of cases to losing control of it very quickly,’’ he says. “The lesson is you need to target functional elimination. You don’t have a mindset that says 15 a day is okay, because 15 becomes 50 or 100 or 200 a day really quickly.’’