As co-chairs of the National Close the Gap Campaign we are privileged to represent 52 First Nations and mainstream organisations, who – since 2006 – have come together as allies to create a national movement committed to ensuring health equity and equality and improved life outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Since 2006, this Campaign has advocated for large-scale systemic reform and a paradigm shift in policy design and delivery to truly empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. And since the inception of the Uluru Statement from the Heart this Campaign has supported the full implementation of its three components – Voice. Treaty. Truth.

Committed to listening to leadership and advice

If we as a nation are committed to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health equity and equality, and if we are committed to closing the gap, then we must also be committed to listening to and hearing the leadership and advice that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples share with us.

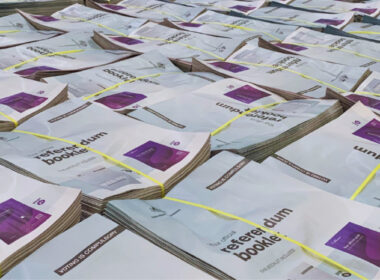

This year our nation will vote in a Referendum, where we will each decide if we want to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution through a representative Voice to Parliament. There are so few moments in time where each of us can look back and know that our one choice propelled our nation forward. And yet, we find ourselves in such a moment.

We each must decide what is right for us, and in the spirit of reconciliation and in the spirit of unity, this Campaign understands that it is our responsibility to contribute to this conversation in an open and healthy dialogue. So, we share with you what we know to be true, so that you can have clarity when you cast your vote.

The reasons for policy and program failings

If successful, the Voice, through constitutional recognition, will allow Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elected representatives to make representations to the Executive and to Parliament. The Executive can choose to incorporate these representations when creating legislation, policy, or program design. Equally, they can choose not to.

But key to this structural reform is that it provides Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with a constitutionally enshrined voice, a permanent seat at the table, and a genuine opportunity to provide advice on matters that directly affect our lives. The intention of the Voice is to change old practices by governments and their agencies. We cannot keep doing more of the same. Large-scale structural reform is necessary if we ever hope to close the gap.

In truth, across the political and policy spectrum there is a tendency to attribute the lack of progress or success of the Closing the Gap Strategy as the individual failures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. But it is in fact systemic political, institutional and policy failures. It is the continual development of poor policies, pursued and implemented by successive Governments, that consistently fail Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities.

This has real and often detrimental consequences. It is felt in our lived experiences, it is visible in our exclusion, and it is crippling this nation’s ability to pursue justice, equity, and equality for all. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities know when policy is harmful instead of helpful, and we know what our own communities need to thrive.

‘We know what our own communities need to thrive.’

Policy and program failings across the broad spectrum of Indigenous Affairs, over decades, are not mistakes. They are the primary features of systems that were built to exclude Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives, cultures, and voices. This is not an oversight, or lack of understanding, it is the inherent nature of current systems.

The result is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are and will continue to be marginalised, excluded, disempowered, and silenced from decision-making processes.

This has real and often detrimental consequences. It is felt in our lived experiences, it is visible in our exclusion, and it is crippling this nation’s ability to pursue justice, equity, and equality for all.

That is why having a representative voice matters.

If Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have that ‘Voice’, we’d have a genuine opportunity to advocate, influence, advise and negotiate, in the development of policy that directly affects our lives. We will have the opportunity to build our knowledges, laws, cultures, customs, love and care for community and country into successful programs in our communities.

As a national Campaign, through our annual reports, we have intentionally focused on the success stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mobs. Firstly, to counter the dominant deficit narrative that frames discourse around Indigenous issues. But, most importantly, to demonstrate that we know what our communities need, and we can and do create enabling and empowering environments for success to be the norm.

At this stage, we do not know how the Voice will directly impact funding, but we do know that the Voice is a necessary mechanism to advocate for what Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples need. We need genuine partnerships, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led decision-making, self-determination, truth-telling and healing. This is what provides the social equity required to bring about improved health and life outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

‘[G]enuine partnerships, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led decision-making, self-determination, truth-telling and healing … [will] provide the social equity required to bring about improved health and life outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.’

Closing the Gap data informs us that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are over-represented in the justice system, have disproportionately higher suicide and child removal rates, lower life expectancy and poorer employment outcomes. In real and measurable terms, there is a lack of health equity and equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across the nation. This is the intersecting nature of disadvantage that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience.

If we don’t create systemic and institutional change to the way that we work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, if we do not have a voice to represent us at the highest levels of government, there cannot be any realistic expectation that our lived experiences would change.

But a ‘yes’ vote could spark that change.

Outside of the Referendum, there is no other proposal put forth that provides the same or better opportunities to drive and embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership and perspectives to create holistic, national, systemic reform. If the ‘yes’ vote is successful, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will be able to make representations, at the highest levels of government, which could be the impetus to improving the health and life outcomes of Australia’s First Nations peoples.

Not an imaginary line

It is not, as has been suggested, special treatment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

No other groups in this nation would be disadvantaged, there would not be a re-drawing of racial lines, it will not create an apartheid-like state. These ideas can sound plausible because they are centred around an obvious truth.

There is a divide between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians. We must be honest and brave enough to see the truth of that statement or we will never be able to provide true equality. The divide is here and if we look close enough, we can see it everywhere.

The Closing the Gap Strategy is an important tool in the way that governments track and measure equity and equality for all Australians. That data is split into two groups, Indigenous and non-indigenous, and it tells us, that across their lifespan, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are disproportionately more likely to experience: poverty, housing and employment instability, youth and adult incarceration, family and domestic violence, poorer health outcomes, and lower education outcomes and life expectancy.

In other words, where we can objectively measure the socio-economic status of all Australian citizens, the data tell us, in quantifiable and in no uncertain terms, that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience disadvantage across a range of identity markers, disproportionately to non-indigenous Australians.

The divide that exists

This is the divide that exists. Not an imaginary line of increased equality for some at the expense of others.

How, with these outcomes, could Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples be more equal than others? How could a reform that provides increased advocacy and representation to one of the most disadvantaged groups in the nation create division?

We all want to live in a more just and equitable society; equity and equality for all does not create division. It creates opportunity.

We cannot continue to have spaces that are void of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s leadership, voices, ideas, and solutions. To do so will only entrench inequality further. It is time governments and their agencies worked with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples rather than ‘doing to’ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.