As time spent alone continues to rise among all demographics, so too does loneliness. Why it’s happening, and how we might change it, is a matter of life and death.

Throughout 2020 and 2021, Melbourne residents spent 262 days in lockdown. For well over 100 days, those in Sydney similarly endured.

The rationale behind the lockdowns, and their intensity, has been debated ad nauseam. Whether the policies were sound, whether the restrictions were too stringent, whether enforcement was too heavy handed … we may never reach consensus. Yet one truth is without doubt: the lengthy lockdowns created an unplanned, unintentional, highly effective natural experiment: what happens when we spend so much time alone?

Over the course of the pandemic, many Australians went days, if not weeks, without seeing another person. The number of daily interactions tumbled, and rates of isolation soared.

Despite best efforts, pixelated faces were an inadequate substitute for physical touch, and ‘social single bubbles’ were no panacea for a prevailing feeling of loneliness. Mental health rates plummeted as we learnt — or perhaps re-learnt — about the importance of physical interaction.

Troublingly, despite more than a year without restrictions, the time we spend alone remains stubbornly high. Though the pandemic was revelatory, it was no catalyst, instead merely exposing a problem that had been simmering for a decade: time spent alone is on the rise.

A loneliness epidemic has followed. And the consequences are literally life threatening.

Social creatures

The story of human continuity is defined by our ability to band together. On the savannahs of Africa, our ancestors were much slower, weaker and smaller than the animals who threatened us. What kept us alive was our superior co-operation.

Just as bees evolved to need a hive, humans evolved to need a tribe, from which separation usually meant death.

With humans having evolved to seek safety in numbers, the brain registers loneliness as a threat. When we are facing unexpected isolation, the parts of the brain that monitor for danger go into overdrive, releasing stress hormones and causing an increase in heart rate, blood pressure and blood sugar levels to provide additional energy in the face of perceived danger.

This ‘fight or flight’ mode is useful when confronted alone by a dangerous predator. But when prolonged, and triggered by chronic loneliness, it can harm our physical and mental health.

When we are facing unexpected isolation, the parts of the brain that monitor for danger go into overdrive, releasing stress hormones and causing an increase in heart rate, blood pressure and blood sugar levels to provide additional energy in the face of perceived danger. When prolonged, and triggered by chronic loneliness, this can harm our physical and mental health.

Loneliness renders people more sensitive to pain, suppresses our immune system, diminishes brain function and disrupts sleep. It increases inflammation and rates of heart disease and dementia. It is more lethal than smoking 15 cigarettes a day or being obese. According to a landmark meta-analysis of 70 existing studies, people who self-identified as lonely had a 26 per cent greater chance of dying in any given year than people who did not.

Humans may no longer face imminent danger when separated from their tribe, but we remain social creatures with physical responses to separation. Disbanding our tribes and telling ourselves that we can do it alone is a key reason for soaring rates of depression, anxiety, and deaths of despair.

‘Bowling Alone’

In 1995, Harvard University political scientist Robert Putnam wrote in the Journal of Democracy of a ‘treacherous rip current’, which, ‘[w]ithout at first noticing’ had caused us to be ‘pulled apart from one another and from our communities.’

Putnam’s essay, ‘Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital’, captured the public’s attention as few academic publications do, telling the story of a massive aggregate loss in the number of people involved in civic and social organisations, and of a decline in engagement with fellow citizens. Although the number of people who bowled had increased between 1975 and 1995, Putnam discovered that the number of people who bowled in leagues had decreased. ‘They were lonely bowlers now, making their strikes without benefit of a hearty clap on the back or a beer bought by the guys’, wrote the essayist Margaret Talbot in a book review.

Putnam attributed some of the erosion in social capital to the rise in double-career families, to ‘suburbanisation’ and other demographic changes. But he laid most of the blame on the television, which he said had ‘individualised’ people’s leisure time, breeding lethargy and passivity.

His writing was deeply evidenced, and his theses appeared sound: time spent with neighbours had fallen, time spent in civic institutions had fallen, and these truths presented serious problems for social cohesion and democracy.

However, despite the changing pattern of social interaction Putnam identified, the amount of time people spent with their friends and family remained constant. We were bowling alone, and watching more television, but we were watching more television together, with our spouses, our children, and even our friends. Rates of loneliness were stable.

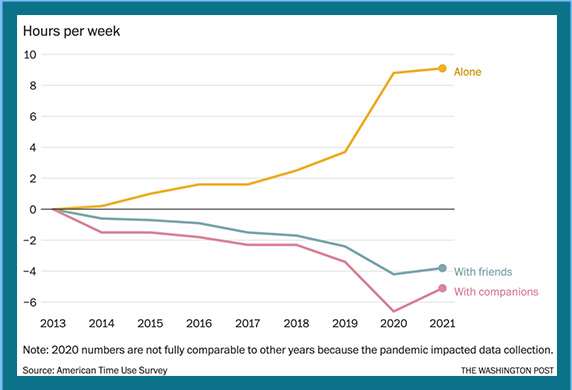

About nine years ago, things began to change. This graph, published in the Washington Post in November last year, went viral.

According to data from the American Time Use Survey, the amount of time people spent with their friends, family and other companions was mostly unchanged between 1970 and 2013. Then, after decades of stability, the numbers began falling. By 2019, on average people were spending almost three hours less with their friends than only six years earlier, and four hours less with their family, neighbours and other companions.

None of that time was transferred to more time with partners, children or others. All of it was swallowed up by time spent alone.

Strikingly, the average American teenager today spends 11 hours fewer with their friends than they did only eight years ago, and 12 hours more time alone. The story is similar in Australia.

Time spent alone, or aloneness, is not the same as loneliness, and for the more introverted it can feel necessary and even joyful. Had the increase in solitude over the past 10 years been entirely voluntary, there wouldn’t be much reason to be concerned. But as time spent alone has increased, so too has chronic loneliness, for people who need people.

While aloneness can be peaceful, loneliness is weighted with shame — a subjective experience of negative feelings about having a lower level of social contact than desired; a lack of meaningful relationships.

According to the Australian Loneliness Report, one in four Australians are lonely, and one in two feel lonely for at least one day each week. Nearly 30 per cent don’t feel part of a group of friends, and more than 20 per cent rarely or never feel close to people.

In 1990, when people were asked how many close friends they could turn to in a time of crisis, the most common answer given was five. Today, the most common answer is zero.

Today’s young people are more educated, less likely to get pregnant or use drugs, and less likely to die of accident or injury than in past generations.

And yet the number of today’s young people who say they are consistently sad and consistently hopeless is at a record high. Anxiety, depression, compulsive behaviours, self-harm and suicide are up, and deaths of despair are up among almost all demographics.

Loneliness is killing us.

According to U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, author of a national bestseller on loneliness:

Loneliness is the underpinning to the current crisis in mental wellness and is responsible for the upsurge in suicide, the opioid epidemic, the overuse of psych meds, the over-diagnosing and pathologising of emotional and psychological study.

The number of today’s young people who say they are consistently sad and consistently hopeless is at a record high. Anxiety, depression, compulsive behaviours, self-harm and suicide are up, and deaths of despair are up among almost all demographics.

So what’s changed?

Several factors may partly explain the trend:

- Parents today are more concerned about safety — not because crime is up, but because reporting about crime is up. The result is that parents are less likely to let their kids play outside with kids in the neighbourhood.

- A lack of urban housing development has pushed people into the suburbs, separated by highways, where public transport is lacking.

- With a higher cost of living, it is more expensive to go out. People work harder with less time for leisure.

But ultimately these reasons are unproven, and at most minor causes for a major rise in loneliness.

While in 1995, Putnam laid most of the blame for us bowling alone on the television, in 2023, the loneliness epidemic can primarily be attributed to our ubiquitous, small, sleek black screens.

In 2013, immediately before time spent alone began trending upwards, market penetration for smartphones in Australia crossed 50%.

Smartphones, tablets, high-speed internet and affordable laptops have catapulted us into a digital economy, where we can work, shop, order food and book holidays without interacting with any other person.

Though we may have bowled alone 30 years ago, we still crowded around the television with our tribe. Today, we stream alone, hunched in a corner of the house watching TV on a phone or a laptop, while our partners and children do the same in their corners, alone.

Streaming TV and movies can be great, but spending 10 hours each week watching them makes us more alone.

Remote work is a godsend for many people, but it also makes us more alone.

As the process of dating moves from schools and offices and bars to individuals messaging each other on phones from couches, it makes us more alone.

When you add it all up, you get a lot more aloneness, and a lot more loneliness.

And the problem compounds. As we interact less in person, we become less comfortable physically interacting, so we do so even less. How often do you turn away as you pass someone on the street, whip out the phone when you get in the Uber, or put on your headphones to avoid an awkward conversation with that person on the train you sort of know? For many, even talking on the phone has become too confrontational.

As the Atlantic’s culture and political writer Derek Thompson says: ‘Relationships are a vaccine for the inevitable malady of the stresses and ups and down of life.’

‘Relationships are a vaccine for the inevitable malady of the stresses and ups and down of life.’

When we don’t invest in our friends and build long-term relationships, it can be harder to lean on our friendships during times of distress. More time alone and less time with people has made us more vulnerable to the stresses of life.

Reversing the trend

Since 1938, the Harvard Study of Adult Development has been investigating what makes people flourish. In the longest in-depth longitudinal study on human life ever done, researchers have studied participants who have ‘fallen in and out of relationships, found success and failure at their jobs, become mothers and fathers.’ Last year, the study’s directors arrived at a simple and profound conclusion: ‘Good relationships lead to health and happiness. The trick is that those relationships must be nurtured.’

According to the study, the number one thing that predicts how long you will live at age 50 is the quality of your social relationships at age 50. Of the 10 global markers of wellness, the most valuable is the existence of a social network. Above all else, the single greatest indicator of happiness is the quality of our relationships.

As the authors write: ‘It never hurts — especially if you’ve been feeling low — to take a minute to reflect on how your relationships are faring and what you wish could be different about them.’

In the course of my research for this article, I have identified the following evidence-based tactics for combating loneliness:

- Each day, invest in personal relationships, because ‘even small investments today in our relationship with others can create long-term ripples of well-being.’

- If possible, commit to helping others. Studies show that people who volunteer two or more hours a week improve their health, ease feelings of loneliness and broaden their social networks.

- Choose an in-person meeting over the phone and a phone meeting over a message. Join choirs, dance clubs, sporting teams or gym classes, civic associations, and even bowling leagues!

- Ask the neighbour for some tomato sauce instead of going to the shops. Order at the counter instead of through the barcode. Pick up the food instead of choosing delivery.

- Watch the same show as your family or housemates, at the same time, together.

- Be consistently curious about people around you. Even a few words exchanged in a supermarket queue or at a bus stop can elevate connectedness and increase wellbeing.

- Keep away from social media as much as possible. Studies have shown that one-third of all smartphone use is undesired — emanating from lack of self-control. People paid by researchers to deactivate Facebook spend more time socialising with friends and family, and when the payments stop, the participants stay off Facebook. We are terrible at aligning our actual behaviour with our ‘hoped-for’ behaviour, but with small incentives we can change.

- Finally, embrace solitude. Connect more strongly with yourself through meditation, prayer, art, music and time outdoors, to enable time spent alone not to feel so lonely.

Of course, many of the forces that pull us apart are hard to combat. Engineers design technology to keep us entranced. Neoliberal social policies have conspired to atrophy our leisure time and create more isolated work environments. It is up to governments, not us, to reign in some of these forces.

But we can play our part in combating the loneliness epidemic. We can become a little more together, and a whole lot happier.