What role did solicitors and their families play in the Australian war effort? Take a look back at the the high cost the legal profession paid at Gallipoli.

When Sydney barrister and soldier Colonel Henry Normand MacLaurin heard in early April 1915 that there was to be a landing on Gallipoli, he cancelled his leave and bounded, grinning, up the stairs of his Cairo hotel to plan the operation. He could hardly wait to command the 4,000 men of First Brigade in battle.

Solicitors, barristers, law clerks, law students and their relatives numbered among these men from NSW who were destined to land on Gallipoli on the afternoon of 25 April 1915. MacLaurin’s excitement was infectious, but his war would not last long. He was shot and killed within two days of the landing.

MacLaurin’s death led to unusual displays of public grief in the legal community. The Chief Justice, Sir William Cullen, presided over a formal service in Sydney’s Banco Court in memory of the high-profile barrister on 5 May 1915. All branches of the law paid tribute to MacLaurin at another service in St Stephen’s Church on Phillip Street on 7 May.

In retrospect, there was great pathos in the service, because the killing time was just beginning and it would affect many people who were in attendance. Justice Street’s son, Laurence, would be killed in action two weeks later. Justice Simpson’s son, George, would fall in 1915. Justice Ferguson’s son, Arthur, would be killed in 1916.

In fact over the eight months of the Gallipoli campaign, 120,000 men would die including 8,709 Australians, 2,701 New Zealanders and 80,000 Turkish soldiers.

The Incorporated Law Institute (which became the Law Society of NSW in October 1960) was represented at the service for Colonel MacLaurin by its president, HC Ellison Rich. Rich’s nephew, John Stanser Rich, the son of Justice of the High Court George Edward Rich, was to be killed at Festubert, in France, fighting with the British Army on 17 May 1915. Everyone among the mourners would be touched by grief in one way or another.

MacLaurin’s death was only the first of many in the legal community, but it was a shocking introduction to the reality of war – a great contrast to the heady days of late August 1914 when he had led the formation of the first NSW contingent of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). It had all begun with such excitement. hen Sydney barrister and soldier Colonel Henry Normand MacLaurin heard in early April 1915 that there was to be a landing on Gallipoli, he cancelled his leave and bounded, grinning, up the stairs of his Cairo hotel to plan the operation. He could hardly wait to command the 4,000 men of First Brigade in battle.

Solicitors, barristers, law clerks, law students and their relatives numbered among these men from NSW who were destined to land on Gallipoli on the afternoon of 25 April 1915. MacLaurin’s excitement was infectious, but his war would not last long. He was shot and killed within two days of the landing.

MacLaurin’s death led to unusual displays of public grief in the legal community. The Chief Justice, Sir William Cullen, presided over a formal service in Sydney’s Banco Court in memory of the high-profile barrister on 5 May 1915. All branches of the law paid tribute to MacLaurin at another service in St Stephen’s Church on Phillip Street on 7 May.

In retrospect, there was great pathos in the service, because the killing time was just beginning and it would affect many people who were in attendance. Justice Street’s son, Laurence, would be killed in action two weeks later. Justice Simpson’s son, George, would fall in 1915. Justice Ferguson’s son, Arthur, would be killed in 1916.

In fact over the eight months of the Gallipoli campaign, 120,000 men would die including 8,709 Australians, 2,701 New Zealanders and 80,000 Turkish soldiers.

The Incorporated Law Institute (which became the Law Society of NSW in October 1960) was represented at the service for Colonel MacLaurin by its president, HC Ellison Rich. Rich’s nephew, John Stanser Rich, the son of Justice of the High Court George Edward Rich, was to be killed at Festubert, in France, fighting with the British Army on 17 May 1915. Everyone among the mourners would be touched by grief in one way or another.

MacLaurin’s death was only the first of many in the legal community, but it was a shocking introduction to the reality of war – a great contrast to the heady days of late August 1914 when he had led the formation of the first NSW contingent of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). It had all begun with such excitement.

Sydney in 1914

At the outbreak of hostilities in the late winter of 1914, Sydney was under the beguiling influence of its most recent aristocratic visitor, Australia’s sixth Governor-General, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson. Two thousand of Sydney’s leading citizens had caught the ferries from Man o’ War Steps at Circular Quay on 31 July 1914 to meet Munro Ferguson at Yaralla, the sprawling Concord estate of Eadith Walker, where he had been living for six weeks.

Assorted solicitors, barristers, judges, businessmen, generals, professors, knights, ladies, gentlemen and their families lined up to shake his hand, reaffirming their loyalty to the Empire in a manner reminiscent of a medieval act of fealty, binding those there to a commitment that would not fail despite what was to come.

War was only days away. News of the declaration of war reached Sydney around noon on 5 August 1914. Many, including lawyers, rushed to enlist. Barrister Geoffrey McLaughlin, the son of solicitor John McLaughlin, was one of the first four men to enlist in NSW.

Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force 1914

The first solicitors to enlist in the First World War joined the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF), which was ordered to occupy German wireless stations in New Guinea. John Malbon Maughan, a 36-year-old solicitor from Neutral Bay, and Albert Henry Edgington, a 30-year-old English trained solicitor from Long Bay, were among the troops.

On 17 August 1914, the men of the ANMEF excitedly marched through Sydney streets crowded with enthusiastic supporters. The soldiers were ferried to Cockatoo Island where they embarked on the transport, Berrima, and rolled out to Sydney Heads the following day, sailing north. Some men had been in the army for less than a week. They trained briefly on Palm Island before action in New Guinea. Captain Pockley, one of the first men to be killed in the war was a relative of the legal family of Herbert Curlewis KC, and well known in Sydney’s legal fraternity, many of whom attended his memorial service

at SHORE school.

First contingent for the Middle East

While the ANMEF battled the heat and a few Germans in Rabaul, Sydney took up the war effort with a passion. Barrister Colonel Henry Normand MacLaurin led the formation of the First Brigade. He had a thriving practice and had been instructed by leading firms such as Minter Simpson (now Minter Ellison), Pigott and Stinson as well as Messrs Sly and Russell. MacLaurin was assisted by a well-known solicitor, Major Charles Melville Macnaghten.

Men enlisted in droves. Soldiers camped at the Sydney Showground and trained near the Kensington sand hills. They often marched through the city streets. MacLaurin and Macnaghten became leading personages in the city.

Many officers in the First Brigade were connected to the legal profession, including Lieutenant Colonel Leonard Dobbin, a 46-year-old Irish-born solicitor and notary with Dobbin & Spier of George Street. He commanded the 1st Battalion. Percy Thomas Owen, the commander of the 3rd Battalion, was the son of the state’s oldest practising solicitor, Percy Owen, who lived on the south coast.

Also among the 1st Brigade when it sailed for war in October 1914 was a 29-year-old Sydney solicitor, Hector Joseph Richard Clayton – later the founding partner of Clayton Utz. He was the son of solicitor J.H Clayton of City Bank Chambers in Pitt Street, Sydney. Hector commanded B Company in the 4th Battalion.

Serving with Hector was his good friend, a 27-year-old solicitor from Mudgee, Bertie Vandeleur Stacy (later a District Court Judge), who had been articled with Dibbs, Parker and Parker.

Clayton and Stacy each had a brother in the medical corps who would serve with them on Gallipoli. Completing the close circle of legal friends, and commanding C Company, was a 26-year-old law clerk, Lieutenant Adam James Simpson, a son of Mr Justice Archibald Simpson of Hunters Hill. Adam Simpson’s older brother, George, would also join the unit and fight with them on Gallipoli.

The first contingent reflected the close-knit nature and common values of the Sydney legal community. Links between the legal profession and the military existed in all manner of ways. The State Commandant for New South Wales, Colonel Ramaciotti, had been the managing clerk in the conveyancing department of Minter, Simpson & Co.

Over the remaining months of 1914 and the beginning of 1915, a steady stream of solicitors, barristers, law clerks, law students and relatives of lawyers enlisted and sailed for war. Solicitors such as John McLaughlin, a former Member of the Legislative Assembly, saw his barrister son, Geoffrey, leave with the Australian Field Artillery. Edward Windeyer, the son of former Justice Sir Charles Windeyer and younger brother to lawyers Richard and William Archibald Windeyer, served with distinction in the 7th Light Horse on Gallipoli. His nephew, Charles, also served on Gallipoli.

Gallipoli: April – May 1915

MacLaurin trained his men hard in Egypt in early 1915 before he led them into battle at Gallipoli on the afternoon of 25 April.

The first day on Gallipoli has always been described as one of fierce fighting and desperate defence, with the Australians constantly threatened with being surrounded and annihilated. The history of the 2nd Battalion describes the time as “a day of epic deeds”.

One of the first of the legal professionals to fall in action was Sydney solicitor Lieutenant Alan Dawson. He was fighting with the 2nd Battalion, not far from Geoffrey Street, who was the barrister son of solicitor J W Street. Dawson was killed fighting somewhere among the thick scrub, trying to break out from the beach up onto the plateau on the first afternoon of the landing. His fate was not uncommon.

Pierce Arthur Goold (known as Arthur) of the 3rd Battalion had been articled to John O’Neill at Murphy and Moloney. Goold was last seen alive, wounded, near the Turkish trenches on 27 April. The 37-year-old’s body was never found. The firm was in deep grief – both members were married to Arthur’s sisters and the lack of any definitive explanation as to his fate ruined his mother’s health.

It was around this time, on 27 April, that Colonel MacLaurin emerged from his dugout above the beach and lost track of where the enemy was in the thick scrub and confused geography.He was shot and killed by a sniper. The surrounding area was known as MacLaurin’s Hill throughout the campaign.

Many lawyers were in action. Major Macnaghten was fighting on the slopes above the beaches in the 4th Battalion with fellow Sydney lawyers Hector Clayton, Bertie Stacy and Adam Simpson. Stacy was commended by his company commander, Hector Clayton, for having “displayed gallantry, coolness and judgment during the whole operation”.

Clayton took the time to write up reports favourable to his men despite his own debilitation from battle. He was always generous in his praise.

The men were in the thick of the fighting in the first days ashore. Adam Simpson survived the attack but was later temporarily evacuated sick from Gallipoli. Stacy was commended repeatedly for acts of conspicuous bravery and service during the entire Gallipoli campaign. He acquired the nickname “Baron Von Stacy” among the men in recognition of his commanding style.

On 19 May, the Turks attacked in force and the men of the 4th Battalion resisted fiercely for days. Young law student Laurence Street was killed in this action (his nephew, former Chief Justice Sir Laurence Street is named after him). The Turkish commitment to repelling the Australian invaders was stated succinctly by their commander, Kamal Attaturk, who had told his men: “I am not ordering you to attack, I am ordering you to die.”

The battles continued as other lawyers continued to land, including the solicitors Lieutenant Arthur Hyman and Lieutenant Reginald Charles Garnock.

In the aftermath of the fight, on 22 May, Hector Clayton was hit by artillery fire as he was sitting in a trench with his officers, including Bertie Stacy. The shrapnel wound exacerbated an already damaged knee. Clayton went to the aid station on the beach where he was attended by his doctor brother, Harry, then evacuated to Lemnos and eventually Cairo.

Clayton had been traumatised by the ceaseless fighting of the previous month. He wrote to his mother describing his experience of Gallipoli as a “hateful dream, a dream of writhing agony, twisted, headless, limbless shapes that were once your men and friends”. Letters such as this, as well as the numerous deaths and injuries to relatives and friends, intensified the legal community’s support for the war into a strident patriotism in which religious imagery sanctified the process.

It was a violent time that cut across the lives of many legal families. Lionel Macnamara was one of three sons of John Macnamara, the founding partner of Macnamara and Smith (eventually absorbed into Stephen Jaques and Stephen in 1936). Lionel was serving with the 2nd Light Horse on Gallipoli. The three Macnamara boys typified the determination of some legal families: Lionel Macnamara was killed in action around 20 May 1915. His twin brother, Brian, was killed in 1917 at Ypres in Belgium. Their older brother Bertie also enlisted, too late for Gallipoli, but was shot and gassed, twice, in action in France. The solicitor, Halse Millett, himself a veteran of the war, would act for the family in the protracted confusion over the certification of Lionel’s death.

On 29 and 30 May, the Turks made a series of attacks on Quinn’s Post, just below the heights of Gallipoli. During the fighting, Major John Brier Mills of the 2nd Australian Field Artillery was killed in action. He was a 45-year-old solicitor, born at St Marys. He practised in Broken Hill, Coolgardie and Perth. His body was located during a careful examination of the battlefields after the war. It’s possible he had been killed while scouting forward to observe the fall of fire onto the enemy attack and was caught in the open by one of the ubiquitous snipers. Mills had been keen. He had fought in the South African campaign and then joined the AIF in August 1914, barely two weeks after hostilities had broken out.

Three days after Mills was killed, Lieutenant Geoffrey Austin Street came ashore again, recovered from wounds. They were tough men – he had been allowed a little less than three weeks to recover from being shot in the head.

A hateful dream, a dream of writhing agony, twisted, headless, limbless shapes that were once your men

and friends”.SOLICITOR HECTOR CLAYTON

writes of Gallipoli in a letter to his mother

Solicitors serving in the British Armed Forces

While most of the lawyers who enlisted went into the AIF, a smaller number had the means and inclination to travel directly to the United Kingdom and enlist into the British armed forces in the hope of getting to the battle front directly, or as a purer form of service to the Empire. Solicitor Keith Williams and his barrister brother, Dudley, later a Justice of the High Court of Australia, were two who went to England to enlist. Long established solicitor Everard Digby had been in Port Said, Egypt, at the outbreak of hostilities. He was accepted into the British Army where he served as a major. His elder son, Lieutenant John L. Digby E.D., M.B., Ch.M., served in France and Mesopotamia with the Royal Army Medical Corps, while his second son, Gerald, joined the 12th Australian Light Horse and served seven months on Gallipoli.

Mervyn Minter, the son of Alexander Robert Minter, senior partner in the firm Minter Simpson & Co, served in the Royal Flying Corps. The other partner in the firm, Percy Simpson, also had a son, Edward, who served with distinction in the Royal Flying Corps, which was something of an elite unit.

Talented law student Adrian Consett Stephen, the son of Alfred Stephen of the firm Stephen Jacques and Stephen (now part of King & Wood Mallesons), travelled to the UK in 1915. He enlisted in the Royal Field Artillery. He was working with the firm Minter Simpson & Co before he left Australia. He served in France from August 1915. Adrian regretted he was not on Gallipoli. He became a poetic observer of the violence and his diary and letters were published after the war.

Stephen wrote to his father of how, on his way back to barracks one evening, “the sunset lit the sky on one flank and on the other the moon rose behind the ruined church – a huge golden ball, and there outlined against the moon, hovering almost around the church steeple, two aeroplanes circled and dived and fought, barking with their maxims (machineguns)”.

Nancy Consett Stephen, Alfred’s sister, became active in the war-related charities along with many other members of the family. Stephen Jacques and Stephen became honorary solicitors for the Red Cross and had a number of staff in the Gallipoli campaign, including articled clerk Graham Cameron, who was with the Australian General Hospital on Lemnos.

He had two cousins killed on the peninsular.

Solicitors on the home front

The Gallipoli campaign was accompanied by dramatic social changes at home. The landings traumatised Australia.

People were in shock and dreaded receiving casualty telegrams delivered by grim-faced clergymen. Death was awful, as was news of wounds or illness. Also devastating and perhaps causing a more exquisite pain (as dramatised in the film The Water Diviner) was to receive news of a loved one missing in action, but with no further details. Even worse was when the fate of a man was telegraphed by an ominous silence where letters simply stopped coming. Imaginations ran riot.

As one grieving mother wrote to the army: “Can you please tell us what has happened to our dear boy?” There were tragic stories of traumatised women going to the docks daily, even after the war, to see if their missing sons had returned.

The legal profession came together to help trace the stories of those lost in action. On 26 July 1915, a well-known senior counsel, Langer Owen KC (the son of a Supreme Court Judge, later a Supreme Court Judge himself, and in time the father of a High Court Judge), presented the idea for a Missing and Wounded Enquiry Bureau at a special meeting of the Incorporated Law Institute in Royal Chambers Castlereagh Street. The proposal was made at his wife Mary’s suggestion. It was to be established under the aegis of the Red Cross.

The Institute agreed to fund secretarial help for the bureau as well as agreeing to circulate a request for helpers. This bureau, whose records are digitised at the Australian War Memorial, provided a much-valued service to grieving relatives and friends of men missing or killed in action. Solicitors and barristers gave their time gratis to act in a role officially designated as searchers, scouring the local hospitals and soldiers’ canteens to elicit information about the fate of the fallen or those missing in action. Lawyers were particularly suited to interview witnesses. Many solicitors gave long hours visiting Randwick Hospital or some of the many soldier’s canteens around Sydney.

A few solicitors, such as H Stuart Osborne, volunteered to work overseas. He travelled to Egypt then Malta with Adrian Knox KC (later Chief Justice of the High Court) to act as a searcher in September 1915. Solicitor William Rand of Rand and Drew in Hunter Street later worked as a searcher in England.

The Sydney population passionately desired to actively help the war effort. The names of well-known solicitors and other lawyers resonate throughout the records of the various committees that sprang up to promulgate appeals.

Some appeals were for money to provide medical supplies through the Red Cross. Others aimed to provide “comforts” for men at the front. Solicitors offered free legal advice to soldiers and their families. One group suggested the formation of a solicitors’ Rifle Club to conduct elementary military training in the Domain. Another suggestion was for a mass event to raise funds, as well as civilian morale, after the shock of the Gallipoli casualty lists.

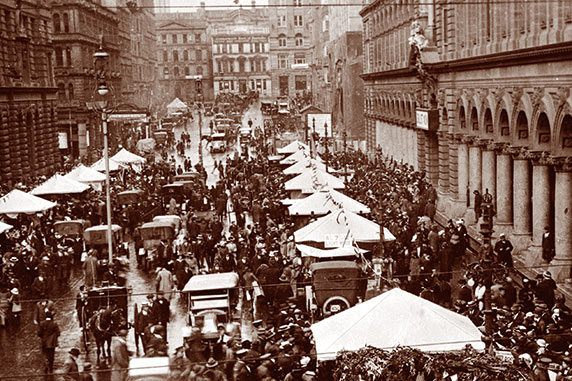

The result was a unique fundraising event on 30 July 1915, known as Australia Day (at the time, 26 January was known as Foundation Day). Such “days” were a common strategy, providing a focus for a particular charity. There had been a Belgian Day on 15 May 1915.

The idea of an Australia Day was suggested by Mrs Ellen Wharton-Kirke of Manly. She was the mother of Errol Wharton-Kirke, a managing law clerk with Ash & Maclean, who enlisted along with his three brothers in April 1915.

The organising committee for the day was led by the Chief Justice, Sir William Cullen, whose son sailed to war in the same unit as one of the Kirke brothers. Australia Day 1915 aimed to raise 200,000 pounds for “comforts” for Australian troops. It eventually raised 839,500 pounds in NSW alone. Much of the reason for such a huge amount of cash, literally collected in bucket loads on street corners and stalls, being forthcoming was the general trust in the community for the lawyers who gave their names to the cause.

The Incorporated Law Institute created and administered its own fund within this program, with some law firms such as Minter Simpson & Co donating up to 200 pounds to the cause. In country towns, solicitors such as J N Moffitt and R D Crommelin at Grenfell organised collections in the local community. The legal profession exhorted the general population to support the various appeals. Solicitor Sep W Dowling from Maclean captured the mood when he wrote to the Grafton Examiner stating he would not go to the local race meeting because he considered it improper that he should enjoy himself when “so many friends and relatives” had been killed or wounded. Instead, he forwarded donations to both the Australia Day and Belgian Funds and urged others to do so.

Solicitor John H Clayton, the father of Hector and Harry who were serving on Gallipoli, wrote a letter to The Sydney Morning Herald railing against people, particularly cricketers, “shirking” their responsibility by not enlisting.

This accusation caused consternation in some quarters as he was the president of the Junior’s Cricket Association at the time. His comment echoed a call, led largely by lawyers, for a program of Universal Service. Lawyers of those days were typically politically very conservative and usually viewed any protest or industrial action as treasonous. Their own willingness to enlist or send their sons to the front gave them credibility when they urged others to do so.

One very successful fund was known as the War Chest. People were encouraged to donate small amounts of cash to street corner collections and various money boxes scattered about the suburbs. Obviously, the steady stream of cash need careful management. The chairman of the War Chest fund was solicitor Allan Hamill Uther (Examiner of Titles, Registrar General’s Department and later the founder of Uther Webster & Evans). His brother and fellow solicitor Gordon served on Gallipoli with the 20th Battalion. War-related activities by lawyers such as Allan Uther are little known but were a highly valued part of the war effort.

Another significant personage in fundraising was the low-profile but highly influential solicitor Edward Percy Simpson of the firm Minter Simpson & Co. Simpson gave generously to charities and manifested a conservative political instinct through support for a right wing group known as the Old Guard.

The result of so much fundraising was the collection of mountains of “comforts” for soldiers overseas. Everything from tobacco to fruit cake and, later, warm clothing could be seen accumulating in piles around the city to be shipped off to Egypt where the mass of materiel had to be sorted and delivered to Gallipoli.

There was not as yet an efficient system to distribute donated goods to soldiers. Such goods were commercially valuable but, more importantly, laden with emotional attachments. Families had donated money and items to go to their much-loved sons, husbands, fathers, cousins and friends on distant battlefields. It was no small thing to disappoint soldiers expecting the arrival of comfort packages.

Similar expectations centred on the donations to the Red Cross, which provided for the wounded or sick. Administration of relief needed strength, diplomacy and efficiency. A number of lawyers were called upon to contribute to prevent a disaster. A particular area of concern, later in 1915, was the handling of goods on Egyptian docks.

The Comforts Fund commissioners were mightily grateful to discover that Captain Hector Clayton, still recovering from his injuries, was in command of the docks in Egypt. Clayton was determined to help the men at the battle front. He had a talent for organisation: he was logical, systematic and possessed a cheerful disposition that naturally encouraged men to work for him. He was greatly praised by those in the Comforts Funds.

He efficiently moved much of the materiel from the insecurity of Egyptian docks to the intended recipients. Clayton was one of many lawyers whose skills would be utilised in headquarters’ duties for the duration of the war.

While more military units left Sydney, new arrivals landed on Gallipoli. On 17 June 1915, reinforcements for the 4th Battalion slipped ashore. Among them was the ANMEF veteran and solicitor Albert Edgington. He arrived when sickness among Australian troops was in epidemic proportions. A month later he was reported siwck with diarrhoea. He was sent to the casualty station on Mudros, then to hospital on Lemnos. His service records show he was “dangerously ill” with dysentery. He died on 20 August – another victim of Gallipoli.

A high price

A dramatic increase in military activity on Gallipoli in August 1915 would affect many lawyers. The August offensives were a last attempt to break out of the ANZAC beach head. The offensives involved such tragedies as the Light Horse Charge at The Nek, the charnel house of Lone Pine, and the often overlooked massacre of the 18th Battalion at Hill 60.

Many Sydney lawyers, such as solicitor Charles Macnaghten, fought in those actions – almost a year to the day after he and many others had pledged their support for the Empire at the Governor General’s Garden party on the banks of the Parramatta River. They fought with their men and squandered their lives to fulfil that pledge.

The legal profession’s commitment to war intensified towards the end of 1915. Chief Justice Sir William Cullen was reduced to tears at a public meeting in Sydney Town Hall when he mentioned his two sons who were fighting on Gallipoli. NSW lawyers were committed to the war. Their sense of the conflict as a holy mission against barbarism was sanctified by the deaths within their own community. Their commitment to the cause sustained them and their families throughout the conflict. It also led to bitter social divisions that marked the national psyche for years to come. Total war came at a high price.