There’s potential for faith in the justice system to be diminished if the legal processes used to mitigate the impacts of intense pre-trial publicity and protect the integrity and fairness of the trial are seen to be a barrier to justice instead of a protection of it.

With a guilty verdict recorded and a killer in jail, The Teacher’s Pet was a win for justice – and true crime. But whether the podcast has improved understandings of the legal system among the general public is much less black and white.

The Teacher’s Pet podcast captivated a nation and millions of listeners around the world, won its makers journalism’s highest honour and, ultimately, helped to catch a killer. A guilty verdict has been recorded as a second podcast series, The Teacher’s Trial, eked out every last morsel of drama during the trial for the true crime-obsessed public. After 40 years, the case is finally drawing to a close and the legal profession is left to ponder the legacy of the landmark, and often divisive, series.

Have the trial and verdict inspired faith in the justice system, or despair that it took so long to reach a conclusion? Does the average punter better understand how lawyers build a brief of evidence or what it means to be a witness in court? How do true crime podcasts like The Teacher’s Pet mediate understandings of the justice system compared to other forms of investigative journalism?

Like the podcast itself, the answers to these questions are complex and often contested. Perhaps the main takeaway is less about past failings of the justice system and instead a call to action that speaks to the future of podcasting.

Risks of engagement

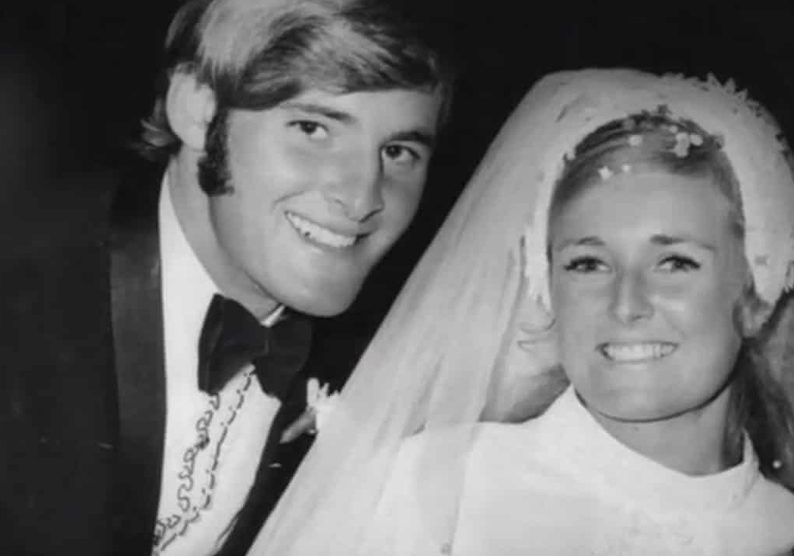

Lynette Dawson went missing from her home at Bayview in Sydney’s Northern Beaches in January 1982. It wasn’t until December 2018 that former professional rugby league player and high school teacher Christopher Dawson was arrested and charged with murdering his wife, Lynette. The catalyst for Dawson’s arrest and subsequent conviction in August 2022 is widely attributed to publicity brought about by The Teacher’s Pet podcast.

Published by The Australian and hosted by journalist Hedley Thomas, The Teacher’s Pet was broadcast between May and December 2018. It reached an estimated audience of 60 million listeners and was the only Australian podcast to reach number one in the US, UK, Canada and New Zealand.

That same year, Thomas and producer Slade Gibson won the prestigious Gold Walkley Award, with the judges describing the podcast as “a masterclass in investigative journalism”. “The investigation uncovered long-lost statements and new witnesses, and prompted police to dig again for the body of Lyn Dawson,” the judges continued.

Why did so many listeners become captivated by the disappearance of a seemingly ordinary suburban Sydney mother-of-two more than three decades ago?

“It had it all,” explains Leah Williams, a lecturer in criminology and criminal law at UNSW. “It was so nostalgic – 1970s and 1980s suburban Sydney, the housewife, the beautiful little kids, the rugby-playing husband. It had the celebrity factor; it had the sex factor. It was a perfect storm of newsworthiness and public intrigue.”

Alison McNamara, legal director at Chamberlains, agrees relatability and intrigue were significant drivers of the appeal, along with the capacity for audience participation. “There were so many calls and so much information that came from the public that ended up being really helpful, and it gave a forum for that,” she says. “It brought the community together.”

As to how intense interest in The Teacher’s Pet translates into knowledge and faith in the justice system, Williams says any format that better engages the public with the criminal justice system can have a positive impact.

“It’s something that very few people experience directly, and the way that people often receive news about it is generally not in a really substantive way,” she says. “There’s certainly benefits to people finding a way to become more engaged with the process and finding impetus to think about the way that the system works.”

Williams says a conviction after 40 years means there’s a clear “justice at last” sentiment associated with The Teacher’s Pet. But as the podcast drifted perilously close to being so prejudicial as to prevent the trial ever proceeding, it almost derailed the carriage of justice – and with it, trust it in the system itself.

“There’s potential for faith in the justice system to be diminished if the legal processes used to mitigate the impacts of intense pre-trial publicity and protect the integrity and fairness of the trial are seen to be a barrier to justice instead of a protection of it,” Williams says.

“There were numerous mentions on The Teacher’s Trial about Dawson’s failure to give evidence and rumination about all the opportunities he had had to give his side of the story. Such discourse frames the right to silence and presumption of innocence as a barrier to the truth and justice.”

Intimate and accessible

The broadcasting of high-profile trials, serialised storytelling and, of course, investigative journalism are nothing new. More than 150 million American viewers – 57% of the country – tuned in to watch the verdict in the O.J. Simpson trial in 1995. First published in 1836, Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers is widely considered the vanguard of serialised fiction.

But it’s the combination of these three elements delivered in a convenient audio format that can facilitate a more intimate, and fundamentally different, relationship between the content, the medium and the audience of a true crime podcast like The Teacher’s Pet.

Dr Andy Ruddock, senior lecturer in Communications and Media Studies at Monash University, says the accessibility of podcasts is one of the simplest and most powerful differentiators when compared with other forms of media.

“One of the things that is unique about podcasts is they are part of the mobile revolution, where media consumption follows us everywhere and therefore reshapes our social spaces,” he says. “We’ve all become quite good at carving out new media consumption spaces for ourselves while doing other things.

“There’s this idea that true crime has always been a profit maker and an audience gatherer, which is something that goes back to newspapers, but with podcasts there’s the accessibility and the emotional relationships that are built around that.”

Williams agrees podcasts like The Teacher’s Trial provide more insights than newspaper court reporting. “It invites the audience to become invested in the trial and in that sense provide a richer opportunity for facilitating community understanding of the process,” she says. “Podcasts can also help to highlight other aspects of the justice system that would otherwise not necessarily reach that same audience.”

Indeed, in The Teacher’s Pet, greater access to the goings on before a case goes to trial helped the audience to better understand the inner workings of the justice system, says James Penny, a barrister at the Victorian Bar.

“As a practitioner, it brought into light a lot of questions that people have about cases, and often questions that people have when decisions are made to charge and not to charge,” he says.

“It highlighted decisions that exist prior to trial which are not necessarily always published, and helped people understand what the process is of compiling briefs of evidence, putting it to the Director of Public Prosecutions and getting advice on whether there’s enough evidence for a conviction or not.”

Leah Williams, Lecturer in Criminology and Criminal law at UNSW

Leah Williams, Lecturer in Criminology and Criminal law at UNSW

Education versus entertainment

There is a fine line between education and entertainment, and a very real risk that the pursuit of one can have a negative impact on the other. “There’s a risk that that sort of approach cheapens and oversimplifies what’s really involved in doing justice,” says Michael Bradley, managing partner at Marque Lawyers. “It can bring a superficial lens to very complex issues and matters.”

What’s more, he says, because true crime podcasts tend to focus on newsworthy cases where the justice system has arguably failed, “it can skew people’s perceptions of how much integrity or credibility it has”.

The entertainment factor can also perpetuate distortions and gaps in representations of crime and reinforce inequalities. Williams cites media fascination with missing white women – dubbed literally “missing white woman syndrome” – as evidence The Teacher’s Pet hasn’t successfully challenged mainstream narratives of crime and victimhood.

“If Lynette Dawson hadn’t been white, if she hadn’t been young, if she hadn’t been wealthier, would there have been the same interest in The Teacher’s Pet?” she says. “What if it had been a First Nations person or a gay relationship – would we have seen this level of public investment?

“Similarly, if there hadn’t been a taboo relationship between the teacher and the babysitter, those more titillating aspects to the story, would it have achieved the success that it did?”

There are, however, some clear upsides to the entertainment offered by true crime podcasts, especially when compared to procedural dramas on TV. Dr Ruddock says intense interest in The Teacher’s Pet has fostered a more nuanced understanding of the justice system. In particular, he says there’s now far greater tolerance for uncertainty.

“There’s always a danger when the facts of the case have to fit the entertainment function of the form, and people are listening because they want to be entertained by a complicated story with twists and turns,” he says.

“But one of the things that’s interesting about the podcasting space is it does seem to be a place where people are open to exploring contingencies. Research on TV shows people conclude that most crimes get resolved, when in fact they don’t.

“With true crime podcasts, you’re never entirely sure what the answer is, so it invites audiences to speculate. It has really introduced this idea of uncertainty into the public realm.”

Charting a shared future

With a guilty verdict recorded and the sentencing hearing complete, where to next for true crime podcasting and the justice system in the wake of The Teacher’s Pet phenomenon?

Penny says the way forward is a commitment to healthy co-existence. “It’s trying to get the balancing act right of people understanding that there is a need for promoting the understanding of the presumption of innocence that exists in our society and our system, against balancing that with people being able to comment on and report on matters in ways they were never able to previously.”

For Dr Ruddock, true crime podcasts are yet another signpost in the evolution of a conflict that’s long existed between the justice system and the media. Adapting to the changing environment is the best approach, he says.

“How do you fight a war when soldiers have got access to social media? It changes things,” he says. “How do you run a justice system in a world of media saturation? It changes things.

“We’re always retrofitting the institution to fit the media, rather than governing the media to fit the institution. So instead of saying, how do we protect the court system from podcasts, it’s more about how the legal system adapts to a new media environment in which podcasts are becoming a significant driver.”

McNamara hopes for a future where podcasting and the justice system “sit side by side in a way where it’s not prejudicial to proceedings if and when they happen”. Bradley says even though there are some “very legitimate criticisms” of The Teacher’s Pet among legal professionals, it’s “not an answer to just shut it down”.

“It’s in the public interest for these stories to be told,” he says. “There are very good reasons to objectively look at The Teacher’s Pet and ask: if it had never been made, would Chris Dawson have ever faced trial?”