It goes with the notion that in order to teach you not to kill, I’m going to kill you.

JULIAN McMAHON,

Barrister

Barrister Julian McMahon is best known for his work with Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran. These Australians were two of eight people executed on an island off the south coast of Java on 29 April 2015. Along with solicitor Veronica Haccou and a senior DFAT official, McMahon was only a few hundred metres away when his clients were tied to a cross. He heard the 96 shots that came in a sudden volley. Now, as President of Reprieve Australia (RA), which works for a world without the death penalty, McMahon is striving to stop state-sanctioned, premeditated killing. JULIE McCROSSIN speaks to McMahon about plans for a new engagement with “people of courage” in the Asian region to abolish the death penalty; why lawyers have a special duty to do this work; the high price paid by human rights lawyers in some countries; and the October 2017 visit to Australia of London lawyer Parvais Jabbar MBE from the Death Penalty Project.

Julian McMahon speaks with precision and gravitas. The predominant principle McMahon communicates in everything he says is a deep respect for the individual and the value of human life, combined with the conviction that there is interconnectedness between the willingness of the state to kill an individual and a broader pattern of state violence towards its citizens.

McMahon believes that when the state engages in brutality, such as hanging or shooting people, it harms everyone involved, including the body politic and everyone engaged in it: from the decision-makers to the executioners, and the families and associates of all involved. Quite simply, the death penalty is an affront to everything he believes in.

“The thing about a premeditated, state-sanctioned killing that makes it so repugnant is that it is carefully planned and completely avoidable,” he says just before he flies to Kuala Lumpur in late July to speak at the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network (ADPAN) Conference. “It goes with the notion that in order to teach you not to kill, I’m going to kill you.”

This repugnance for state-sanctioned killing underpins his work for Reprieve Australia. Reprieve conducts advocacy and raises awareness, including speaking in schools and across the community about the rule of law and executions. Reprieve also arranges for volunteer lawyers and interns to provide legal and humanitarian assistance to lawyers and prisoners in the USA.

“The primary activity of Reprieve until recently has been to recruit and send volunteer lawyers to the southern parts of the United States,” he says. “This is principally because one of the founders of Reprieve, Melbourne barrister Richard Bourke, now works in New Orleans. For the past 15 years or so, Reprieve has sent more than 100 volunteer lawyers to work in law offices which are swamped with too much work, too many cases, too few lawyers and too few resources.

“Our intention now is to do similar work in our region and to engage in a multifaceted way with individuals and organisations working against the death penalty in our region.

“We want to partner up with universities, for instance, to have targeted and useful research in areas which will then provide information, data and assistance to people, such as MPs and lawyers, who are able to engage in the debate across the region.”

JULIAN MCMAHON

JULIAN MCMAHON

This new direction in our region is delicate work for McMahon and his colleagues. They want to partner with policy makers, decision makers and, wherever they can, lawyers fighting cases on the ground in the courts. This is in a region where ADPAN, a network founded in Hong Kong in 2006, estimates that more people are executed in the Asia-Pacific region than in the rest of the world combined. ADPAN says 13 countries in the region have carried out executions in the past 10 years.

McMahon was a tutor in Classics in the Arts Faculty at the University of Melbourne’s Trinity College in the late 1980s. He completed an Honours Arts degree in Latin and Ancient Greek, before studying law at Melbourne, followed by a Masters in Law at Monash.

These days, he is deeply involved in this international work. He attended the general assembly of ADPAN late last month and, in June, Reprieve joined the steering committee of the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty in Washington.

“One of our guiding principles is that we need, at all times, to be both courteous wherever we go and respectful of the people and systems we are dealing with. Without that courtesy and respect, we will fail,” he says.

Central to this work is the goal of the reduction of state violence of all kinds. McMahon offers two very different national examples to illustrate the connection between the death penalty and a broader pattern of state violence: China and the United States.

“In China, despite all kinds of development and progress, there is a constant, widespread pattern of allegations of brutality against many prisoners when they are arrested,” he says. “This includes torture. There are multiple examples of state oppression and violence, whether against human rights activists or people simply trying to assert their rights against corrupt officials.

“Combined with that, you will also find China’s willingness to execute in large numbers, probably several thousand a year or more. So, in China and many executing countries, there is interconnectedness between arresting people violently, treating them violently, and being willing to kill.”

The recent anniversary of the so-called “709 Crackdown” in China illustrates for McMahon that people who fight the death penalty and for human rights need to be “people of great courage”.

Two years ago in China, on 9 July 2015, hundreds of human rights lawyers, legal assistants and activists were taken into custody and interrogated. Many have been released over time, but some are still “disappeared”.

In an article to mark the anniversary of the arrests, the South China Morning Post reported that some lawyers were still facing trial for subversion and families were unable to visit them. Some of those released described torture, forced use of medication, and mental deterioration. (“China’s human rights lawyers continue to fight for victims of the ‘709 crackdown’. South China Morning Post 9 July 2017.)

“Any lawyer engaged in human rights work in China is automatically a person of great courage,” McMahon notes.

“We see in countries such as Iran the attacks on lawyers and people fighting for human rights. Across country after country, we’ve seen community and political leaders having to simply be courageous.

“You realise how much courage is involved to stand up and fight for rights. Everyone has a duty to take action to end injustice.

“However, state-sanctioned killing operates according to law and, accordingly, lawyers are well placed to provide a critique of that law and of the flaws of justice systems. Lawyers have a special duty to explain the fallibility of all justice systems.”

The legal history of the United States offers a very different insight into the relationship between the death penalty and the use of violence more broadly, McMahon says.

“If we look at the south of the United States, there is increasing scholarship and evidence linking different kinds of violence,” he says.

“The reality of how black Americans were treated over the past 150 years still plays a role in the injustices today.

“Scholars now talk about a link between the end of the era of slavery, the increase in the number of lynchings in the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, and the burgeoning numbers of black Americans who were executed once the period of lynching was over.

“Then we can look at the Black Lives Matter movement and the number of examples of violence against black Americans.

“There is a culture of violence that is undeniable and it is linked to a willingness to execute.” (See A Presumption of Guilt by Bryan Stevenson, The New York Review of Books 13 July 2017 issue in which a black lawyer reflects on the historical context of his own experience with police in Atlanta).

It is these patterns of deep-seated cultural and historical violence, and its manifestation in the legal systems and the use of the death penalty, that McMahon is seeking to expose through a long process of international partnership, engagement and activism.

Yet, at a deeper level, underpinning all this international work is a commitment to the rights of the individual under the rule of law. This is especially clear when McMahon speaks about the biggest death penalty case he has been involved with so far: the cases of Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran in Indonesia. In a widely-quoted comment at the time, McMahon said he had urged the two young men facing the death penalty to engage in “serious self-reflection” and said, “They had a choice to live like fools or live like men”. This doesn’t sound like standard legal advice. McMahon explains the context of these remarks. He acknowledges that lawyers strive to keep a professional distance in a similar manner to doctors or ambulance officers. However, in some cases, there can be a particular intensity with death penalty cases that may run over several years.

“In addition to the normal legal arguments revolving around questions of matters of proof, law and the constitutionality of executions and so on, we have the reality of dealing with two intense young men, in a complex, difficult and dangerous environment, where crime and drugs are an everyday occurrence,” McMahon says.

“Andrew Chan was getting involved and finding fulfilment in his Christian groups, so my remarks probably at the time referred more to Myuran Sukumaran.

You realise how much courage is involved to stand up and fight for rights. Everyone has a duty to take action to end injustice.

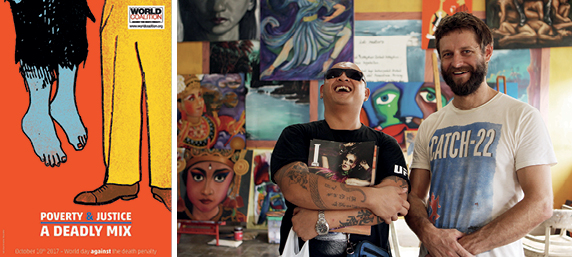

“Things were less clear for Myuran. He was a person who had begun to think deeply and was hungry for self-knowledge and an understanding of the bigger picture. How did he come to be in this situation and was he going to die soon? It was a natural evolution to say he had to make choices to live a life of foolishness or to live a life of good value.

“He gradually came to understand that by leading a life of courage, hard work and generosity in the prison, he would be proud of himself, enjoy whatever time he had left, and make his family proud of him. Around that time he began to develop his interest in art. So both things fed each other.”

There is something deeply humane about McMahon’s engagement with his clients’ transformation and the needs of their families. It is this professional engagement that underpins his broader efforts to end state violence.

As part of this broader work and desire to engage the legal profession in Australia and community leaders more broadly, McMahon and Reprieve Australia are inviting the executive director of the London-based Death Penalty Project to Sydney and Melbourne in October for some special fundraising events.

Parvais Jabbar was awarded an MBE for his service to international human rights in 2012 and he specialises in criminal litigation, constitutional law, international human rights law and prison law.

The Death Penalty Project, according to McMahon, probably has been the most effective legal team in the world fighting mandatory executions for 25 years. Watch out for these events on the Reprieve Australia website reprieve.org.au