The inclusion of a Voice for First Nations people in the Constitution, to be decided by national referendum in the coming months, has been debated intensely.

At the Law Society of NSW’s NAIDOC Week event on 6 July, attendees heard how lawyers play an important role in promoting accurate messaging about the Voice. Event speaker Jody Broun, Yindjibarndi woman and CEO of the National Indigenous Australians Agency, urged lawyers to take two actions: to become fully informed about the Voice, and to share that knowledge with their connections.

It is very difficult, however, to find a way through the maze of information, opinions and misinformation shared since Prime Minister Anthony Albanese declared in his election night victory speech in May 2022 that a referendum would be held on the Voice.

As Luke Beck, Professor of Constitutional Law at Monash University, said in a recently published article in The Conversation, “misinformation and disinformation are a feature of some of the public discussion.”

This is unavoidable, Beck advises – for there are no laws preventing false claims about the proposed constitutional amendment, just as there are no laws preventing misinformation being shared during federal election campaigns.

The prospect of major national change can cause a sense of uncertainty and fear, and lead to the airing of worst-case scenario views. Through interviews, research and consultation, LSJ has compiled this set of themes to clarify the issues people are voicing. We hope it will help you to make an informed decision about voting in the referendum, and support others in your network to do so.

1. Inclusion of a Voice in the Constitution

The call for the Voice came from a large group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders.

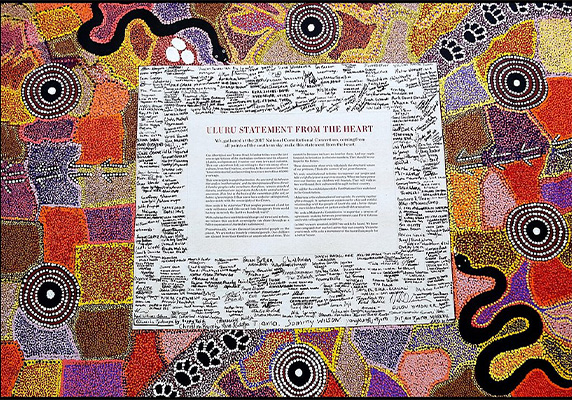

At the National Constitutional Convention in 2017, 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders met at the foot of Uluru to “seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country”.

These words helped to form the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which emerged from the gathering and called for “the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.”

The purpose and power of the Voice is described in the wording for the referendum:

“In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

-

- There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.”

The link between Voice, Treaty and Truth

Indigenous leader Thomas Mayo and journalist Kerry O’Brien said they wrote the Voice to Parliament Handbook in part to dispel “the fear mongering [that] is similar to what happened when Mabo happened and the Native Title negotiation.”

The Uluru Statement from the Heart is a call by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for real and practical change in Australia through the establishment of a constitutionally enshrined Voice to Parliament.

“Embodied in the Uluru Statement,” said O’Brien, “is a request for three fundamentally important but quite reasonable things. First among them is to have constitutional recognition of First Nations people. This would permanently ensure their right to have a Voice to the Australian Parliament and Executive Government when it is considering passing laws that will have an impact on them. Not a Voice in the Parliament, but a voice making representations to the Parliament.

“The other two elements of the Uluru Statement are the process for truth-telling about Indigenous history and for agreement-making, the Makarrata. These elements, under the guidance of a Makarrata Commission, would not require constitutional change and would be created through an Act of Parliament.

“This is not something that we haven’t seen before in Australia, but what we haven’t seen before is that the Uluru Statement from the Heart is now leading us through a referendum.”

A step in the right direction

For many in Indigenous communities, the Voice is seen as a partial solution to address two centuries of “the torment of our powerlessness,” as expressed in the Uluru Statement.

According to Reconciliation NSW, “First Nations people have been calling for meaningful change for many years. This referendum is a step in the right direction.”

Marcus Stewart, a Nira illim bulluk man of the Taungurung nation, is a negotiator and strategist, and Co-Chair of the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria.

He said that the Yes23 Campaign is “an important practical first step towards getting things right for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the future.”

A mechanism within the structures of the state

The Voice, said Cobble Cobble and South Sea Islander woman Megan Davis, “offers a formal means to address issues relating to First Nations people, enabling them to submit those issues for examination and management within the legislative system.”

Davis is Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous UNSW, a Professor of Law at UNSW, an international human rights lawyer, and a co-author of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

“It should not be the case,” she wrote in her recent Quarterly Essay, “that street protest and media activism are the only ways Indigenous people can be heard.”

“The Voice,” Davis wrote, “will be a mechanism to demand attention that sits within the structures of the state. It will allow the Indigenous community to flag issues that are important to them; they will have the ability to recommend that a representation is made about the issue by the Voice to the government or parliament.

“This means the ground level impact of policies and laws upon families and individuals can be properly and seriously ventilated in situ with the Parliament. The gravity of such a representation, particularly on matters that are causing a huge amount of suffering and community disharmony and sadness, will guarantee a response.”

A compelling invitation to government

Whadjuk Noongar woman Narelda Jacobs, a journalist and television presenter, believes “issues the government choose to highlight are selected because politicians act on things that are popular” and that those representatives of electorates in turn focus on areas that will affect their chances of re-election.

Jacobs described the Statement as “this beautiful statement, the Uluru Statement from the Heart, after years and years of consultation, [this is] something that was also done in the late 70s and early 80s in the days of my father, when the National Aboriginal Conference did the same thing to create a plan for a Makarrata.”

Enshrining a Voice in the Constitution, said O’Brien in The Voice Handbook, “doesn’t eliminate the risk of indifference from the government of the day but it certainly reduces it.”

For Davis, the Voice and the Uluru Statement are more than that: a way to move government attitudes from indifference to active engagement.

“On the Uluru Statement from the Heart and a constitutional Voice to Parliament,” she wrote in her Quarterly Essay, “Australians could see an unconventional yet compelling invitation to address one of the most acute challenges for Indigenous Australians: getting the government to listen.”

‘An unconventional yet compelling invitation to address one of the most acute challenges for Indigenous Australians: getting the government to listen.’

Best placed to solve these problems

Proponents of the Voice believe it is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities who should be identifying and addressing problems in their communities.

The Yes23 Campaign said, “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people know and understand the best way to deliver real and practical change in their communities.”

According to Closing the Gap, “When Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a genuine say in the design and delivery of policies, programs and services that affect them, better life outcomes are achieved.”

“Our communities live these problems,” said Empowered Communities, an alliance of 14 Indigenous leaders from 10 remote, regional and urban indigenous areas in NSW, Western Australia, Victoria, Northern Territory and South Australia.

“We are best placed to help solve them. [The Voice will] empower local communities to partner with government to develop better solutions.”

O’Brien wrote in the Voice Handbook, “one key reason why Indigenous policy has failed so fundamentally at times is because it has been written and implemented from Canberra by non-Indigenous politicians and bureaucrats, without listening to the people they’re supposed to be helping.”

2. Lack of detail about the Voice for the referendum

It has been claimed the lack of detail about the Voice in the referendum question is a shortcoming and will make the Voice ineffective.

The referendum question has been worded as follows:

“a Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait voice.”

This is the correct procedure, said Wakka Wakka/Gunggari man Kevin Williams, a lawyer, educator and Visiting Elder.

“The question must be brief, as is required by the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984, which provides the framework for the conduct of referendums,” Williams told LSJ.

Lawyer Mark Leibler was co-chair of both the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians that reported in 2012, and the Referendum Council that culminated in the release of the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017.

Leibler told LSJ the current lack of detail about the Voice is that it depends on the input of Parliament, and this will take place only after the inclusion of the Voice has been decided on.

“Only the principle of the Voice will be in the Constitution,” Leibler said. “All the detail about its form and function will be legislated by the parliament and amended by legislation if and when required.

“Parliament will finalise the details of the Voice after the referendum and that is exactly how it should happen.”

The Voice, which is a simple enabling provision in the constitution, is regarded as both substantive and symbolic recognition, Davis said.

She explained in her Quarterly Essay: “Recognition can come in a weak form, such as symbolism. (It’s weak because it does not change the status quo.) Or it can be a strong form, such as designated parliamentary seats, a voice or even an autonomous region.”

‘Recognition can come in a weak form, such as symbolism … it does not change the status quo. Or it can be a strong form, such as designated parliamentary seats, a voice or even an autonomous region.’

“The ‘No’ case,” Mayo and O’Brien said, “is asking questions about details that are not letters for the referendum, such as the technicalities of how Indigenous Representatives will be elected to the Voice and what the Voice may make representations on.”

The referendum, however, the co-authors said, “is only about establishing the principle that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should have a voice. The rest will be determined by the Parliament.

“The camp that calls for more detail misunderstands what is at stake. Calls for details have come from MPs who say they need information on, for instance, how members of the Voice will be elected, or what exact functions and powers it will be given. But the Australian electors will vote on the constitutional outlines, not on this detail.”

In an Australian Financial Review article in February 2023, Gabrielle Appleby, Professor, Faculty of Law and Justice at the University of New South Wales, and Ron Levy, Associate Professor, College of Law at the Australian National University, outlined as follows the function of Constitutions, and the requirements relating to detail:

“Constitutions create living, evolving institutions. They lay strong and deep foundations, but they do not set in stone the make-up of institutions. The parliament, the government, the courts, the military – all these are spelled out in our Constitution at best with basic detail. The detail, rather, is provided by the parliament through legislation, which may be challenged in the courts to make sure that detail conforms with the basic structure in the Constitution.”

Lecturer Katie O’Bryan and Professor Paula Gerber from Monash University’s law school advised, “There’s already a detailed report that sets out what a legislated Voice could look like: the Indigenous Voice Co-design Process Final Report.”

3. What the Voice will look like

- It will be a permanent body that gives independent advice to the Parliament and Government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- It will be chosen by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people based on the wishes of local communities, not by executive government.

- It will be representative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, gender-balanced and include youth.

- It will have its own resources to allow it to research, develop and make representations.

- It will be empowering, community-led inclusive, respectful and culturally informed.

- It will be accountable and transparent.

- It will work alongside existing organisations and traditional structures.

- It will not have a program delivery function. It will make representations about improving programs and services but will not manage money or deliver services.

- It will not have a power of veto.

- Members will serve on the Voice for a fixed period, to ensure regular accountability to their communities.

- To ensure cultural legitimacy, members of the Voice would be chosen in a way that suits the wishes of local communities, determined through the post-referendum process.

- In terms of representation, members would be Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and they would be chosen from each of those states and territories.

- The Torres Strait Islands would have remote representatives as well as mainland representatives.

- If the referendum is successful the detail of the structure and function of the Voice will be determined by elected members of Parliament, through the normal processes of debate and legislation.

- After a successful referendum, there will be a consultation process, across the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, Parliament and the public, to determine the design of the Voice.

4. The case being made for the ‘No’ vote

Some proponents of the “No” vote see the inclusion of the Voice in the Constitution as acceptance of rule by a government rooted in colonialism.

In this view, First Nations sovereignty over the land has been ceded to Crown sovereignty.

Lidia Thorpe, Djab Wurrung Gunnai Gunditjmara woman, Independent Senator and face of the Blak Sovereignty Movement, said, “Our sovereignty does not coexist with the sovereignty of the Crown … We are the original and only sovereign of these lands.”

Thorpe said First Nations people had “never agreed to be governed by the colonial Australian government” and they do not “acquiesce or surrender”.

“We do not want to be part of the colonial constitution and the attempt to rule over us and our land,” she said.

“We don’t accept any colonial mechanism that continues to control us, which is what the Voice ultimately is a part of. It has no power, it will be controlled by the parliament.”

In contrast, many hold the view Indigenous sovereignty cannot be ceded by constitutional recognition.

Noongar woman Hannah McGlade, a member of the United Nations Permanent Forum of Indigenous Peoples, said, “Nowhere does the Voice to Parliament proposal suggest any agreement of Aboriginal people to cede sovereignty.”

‘Nowhere does the Voice to Parliament proposal suggest any agreement of Aboriginal people to cede sovereignty.’

Indigenous leader Thomas Mayo, signatory to the Uluru Statement from the Heart, said he understood sovereignty would always be retained. “If there is a successful referendum,” he said, “I, Thomas Mayo, will not wake up the next day and no longer be a Kaurareg Aboriginal and Kalkalgal, Erubamle Torres Strait Islander man.”

Among his previous roles, former Chief Justice Robert French was president of the Australian Association of Constitutional Law. At the Exchanging Ideas Symposium held by the Judicial Commission of NSW earlier this year, French said, “Authority over land and waters within the First Nations legal framework and within the colonising legal framework are capable of co-existence just as tradition law and custom are capable of co-existence of the kind reflected in native title agreements.

“Importantly, constitutional recognition and the creation of the Voice does not involve any ceding of traditional authority over land and waters.”

Privilege vs democracy

It has been claimed by the “Fair Australia” campaign that the Voice would privilege one group over another: “It is by definition an extra right and an extra democratic power for one group of Australians over another.”

In contrast, Commonwealth Solicitor-General Stephen Donaghue noted democracy would not be compromised by the Voice. He said, “the wording of the amendment to the constitution poses no threat to Australia’s democratic system of government.”

In the view of the Yes23 Campaign, a Voice to Parliament would “simply ensure that Indigenous people affected by decisions made about them are able to advise politicians about what really works in their communities.

“This will not create special privileges for Indigenous people that others don’t have. Rather it is a first step towards building a stronger relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.”

A question of divisiveness

It has been claimed the Voice is divisive. The Advance Australia campaign said, “When the Uluru Statement talks about co-sovereignty and self-determination make no mistake: it isn’t making a symbolic point. It means separate laws, separate economies, separate leaders. That is: separate countries.”

It has also been suggested, by former politician Warren Mundine, for example, that the vote should be ‘No’ unless culturally diverse groups are also given a Voice.

However, the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia (FECCA) and Multicultural Australia published a Joint Resolution of Multicultural Community Organisations in support of a First Nations Voice, stating:

“As leaders of diverse multicultural community organisations, we endorse the Uluru Statement and its call for a First Nations voice guaranteed by the Constitution. This reform is modest, practical and fair.”

FECCA Chair Carlo Carli said the call to extend the Voice to multicultural communities is divisive: it could result in immigrants being pitted against Indigenous Australians.

A diversity of opinions in communities

“Within any group of people, there will always be diverse perspectives on political matters,” said a group of Edith Cowan academics from the faculty of Psychology and Social Science and the University’s Centre for Indigenous Australian Education and Research.

‘Within any group of people, there will always be diverse perspectives on political matters.’

“Of course, First Nations Communities do not have a homogenous view on the Voice,” said Awabakal woman Kate Russell, board director on the NSW Aboriginal Land Council and CEO of Supply Nation from 31 July. “We are a diverse group and have different opinions on how we want to advance.

“But First Nations people do overwhelmingly support the Voice.”

Jacobs said that diversity of views across Indigenous Communities is to be expected. “There are First Nations people involved in every facet of decision making, whether it’s grassroots protesters, activists who are pushing a more radical way of thinking and doing things, all the way up to very conservative people who have the ear of government and decision makers.

“But we need to be able to hear everyone. Everyone down the line. We need to be able to hear what their wants and concerns are.”

The Uluru Statement from the Heart, from which the concept of the Voice emerged, was a process of extensive consultation that culminated in a National Constitutional Convention at Uluru in 2017. This was, in the words of the Uluru Dialogue, the “most proportionally significant consultation process of First Nations peoples Australia has ever seen.”

Mayo and O’Brien outlined the process in their Handbook. Twelve Dialogues and one regional meeting were held, and “the deliberations were conducted over many days, through Regional Dialogues that culminated at the Uluru National Constitutional convention. The authors described this process as “the most extensive, well-informed and well-formulated constitutional dialogues Indigenous peoples have ever had.”

Jacobs said, “When you look back at the Uluru Dialogues travelling around the country, and you look at the people in the room, the community that was being visited – that’s what consultation is all about. It was about going out to as many people as you can, hundreds and hundreds of people, hearing their input, hearing from all the people what they want.”

A sense of disenfranchisement

Jacobs offers a sense of disenfranchisement as a reason for the hesitancy by some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to support the Voice: “Most First Nations people who are hesitant to support the Voice think that it’s not going to go far enough. They are saying, ‘well, what’s the point of having an advisory group if we’re not going to be listened to?’”

“And that’s because they haven’t been listened to. We haven’t been listened to. There’s been no government that’s really listened to us and given us what is needed.

“There have been governments that have come close with Treaty, and then swapped that out for Reconciliation.

“It’s that disenfranchisement amongst First Nations people that has led to disengagement, and that in turn has led to distrust of authority. I think that is what is fuelling a lot of the apprehension amongst Indigenous people, because we’ve been in this position before.”

5. The cost of the Voice

One of the arguments presented against the Voice is that both the referendum process and subsequent decision-making processes and programs would come at a high financial cost to the non-Indigenous community.

These claims are being made on the back of evidence indicating that historical programs specifically targeted at Indigenous communities have been costly and ineffective.

The authors of the Handbook responded to this claim by saying that “many expensive, often well-intentioned policies to address the social and economic inequities directly affecting far too many Indigenous people have failed … because they are often conceived and executed from the centre of government and rubber-stamped by parliaments far away from the communities they’re supposed to be helping.”

The latest Federal Budget, handed down in May, allocated $364.6 million of spending between 2023 and 2026 to help deliver the referendum on the Voice.

As part of the funding, $336.6 million will be provided over two years to the Australian Electoral Commission from 2023–2024 for its role in delivering the referendum. That amount includes $10.6 million for information pamphlets that will be sent out to households detailing both the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ cases.

The National Indigenous Australians Agency and the Museum of Australian Democracy have been allocated $12 million over two years, for “neutral public civics education and awareness activities”.

The National Indigenous Australians Agency will also be granted $5.5 million in the next financial year for “for consultation, policy and delivery”.

The Department of Health and Aged Care will be allocated $10.5 million in 2023–2024 to increase mental health support for First Nations people during the referendum period.

Federal Health Minister Mark Butler explained this funding is needed to address concerns the referendum could follow the path of the 2017 marriage survey, which saw an increase in vilification of and mental health issues among LGBTQ+ Australians.

The Parliament of Australia’s Budget Review Index for 2019–2020, written by James Haughton, outlines the relative costs of programs for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians – and reasons for the discrepancies.

“Over the last decade, total government per capita expenditure on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [has been] approximately double the per capita expenditure on non-Indigenous Australians,” the Review stated.

“The main driver of Indigenous expenditure is not Indigenous-specific programs, but higher use of all government programs. Some of this higher use is due to demographic differences – for example, Indigenous people are on average younger and have higher fertility rates than non-Indigenous Australians, leading to more per-capita demand for pre-school, school and university places, and child care services. However, much of it is caused by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s higher levels of disadvantage, leading to higher use of hospitals, social security, and social housing, as well as higher rates of child protection interventions and imprisonment.

“These circumstances give rise to demand for Indigenous-specific programs … to divert people from these undesirable outcomes. Government per capita spending on Indigenous people and programs can be expected to remain above the per capita average in future budgets until there is real progress on closing the gaps.”

External and international research corroborates this finding. For example, researchers on access to primary health care for Indigenous people, writing in the International Journal for Equity in Health, said, “Evidence suggests that access to primary health care can be improved when services are tailored to the needs of, or owned and managed by, Indigenous communities themselves.”

‘Evidence suggests that access to primary health care can be improved when services are tailored to the needs of, or owned and managed by, Indigenous communities themselves.’

6. How the Voice will affect Closing the Gap targets

Data from Canada has shown that those First Nations populations that run their own services (health, education, welfare etc.) not only have better services, but also the rates of youth suicide are much lower. Similarly, a 2020 study across Brazil, Chile, Australia and New Zealand showed that, where Indigenous people participated in decision-making and program and policy design, this helped ensure barriers to health services were appropriately addressed and also promoted the rights of Indigenous peoples to self-determination.

“While Kevin Rudd’s apology in Parliament in 2008 to the stolen generations survivors was a powerfully symbolic gesture at the time,” O’Brien said, “the government’s commitment to closing the gap in all the headline areas of Indigenous disadvantage has had limited success in the 15 years since.

“The issues that led to the intervention might have been handled much more effectively if Indigenous representations had been available to the Howard government from an advisory group like the Voice.”

Closing the Gap Co-chairs June Oscar and Karl Briscoe prepared this article for LSJ on the link between the Voice and the Closing the Gap outcomes.

7. The difference between the Voice and the voice of Indigenous elected members of Parliament

Jacobs said, “We often hear the argument: ‘First Nations people already have voices in Parliament. And we’ve got so many more Indigenous members of Parliament now than we used to have.’ There are many voices in Parliament, yes, but they all have an agenda. After all, they are representing their electorates, and they want to be re-elected.”

In their Handbook, O’Brien and Mayo supported this view. “Indigenous politicians [would] necessarily prioritise what the voters in their electorates want, not the specific priorities of Indigenous peoples.”

The Yes23 Campaign stated, “Indigenous Australians directly elected to the parliament are elected to represent all their constituents, not just the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in their electorate.”

A constitutionally enshrined Voice, said Yes23, will be “above the usual party politics, and representatives will be solely focused on the issues and will be directly accountable to Indigenous people on the ground.”

O’Brien and Mayo noted that the current number of Indigenous members of Parliament is subject to change. “If [Indigenous Australians directly elected to parliament] are members of a political party they will represent the policies of their party, such as Labor, Liberal, National or the Greens, none of which has a significant number of Indigenous members. The same would apply if they were Independents. Also, while there are eleven Indigenous parliamentarians today, the next election could easily reduce those numbers, based on the mood of electorates dominated by non-Indigenous voters.”

In contrast, the Voice advisory group would not be bound by any single political agenda. Jacobs said this would be “a completely independent body, composed of many people, that represent Indigenous communities. And the only agenda they would have is to service their community members. Not their electorate, not their party, not their political ideology, but what their community needs, what their community is asking for.”

‘What their community needs, what their community is asking for.’

8. Potential challenges to Australia’s court system?

It has been claimed that the Voice will be able to make representations about an unlimited range of matters, which will give rise to time- and resource-wasting ligation.

O’Bryan and Gerber said, “How Parliament responds (or does not respond) to any representations made by the Voice would be non-justiciable – that is, it could not be subject to any court challenge. This is because the courts have always been reluctant to interfere with the internal workings of Parliament.”

Former Chief Justice French and Geoffrey Lindell, Emeritus Professor of Law at the University of Adelaide, wrote in the Australian Financial Review that the Voice may make representations about “matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’.”

“The term ‘relating to’,” French and Lindell said, “can cover a broad range of matters. Its limits are likely to be defined by common sense and political realities. Laws, policies and practices relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education and training, family and social welfare, health, remote community services, community policing, Aboriginal art, cultural and heritage protection, traditional ownership of land and waters, are well within that range.”

French observed, “there is little or no scope for constitutional litigation arising from the words of the proposed amendment [to include the Voice in the Constitution]. The amendment is facilitative and empowering.”

A recent Facebook post claimed, “The voice will give Indigenous people the right to change anything that parliament approves by taking it to the High Court”. This was examined by AAP FactCheck, which gave the following verdict: “Misleading. Experts say High Court challenges are unlikely. If one does eventuate, the court cannot change a decision made by parliament. It can only send a matter back for reappraisal.”

Visit the LSJ portal on the Voice here