After a high-profile cold case was solved in the US by matching DNA on a public genealogy website, excitement grew for the potential of ancestry mapping as a sleuthing weapon. But how can its potential be harnessed in the face of legal and ethical murkiness?

Brandy Jennings thought little of her decision to upload her DNA sample to a genealogy website – and, with a click of a button, cracked a 40-year-old cold case murder.

“My half-brother had composed our mother’s family tree, but I was missing my dad’s side,” Jennings tells LSJ from her home in Vancouver, Washington.

“He died in 2009 and I don’t know a whole lot about his family … I was told about GEDMatch [a public website that allows users to submit their genetic material and search for relatives]. It takes a little bit of time to upload and analyse your DNA and I quickly forgot about it.

“I asked [my brother] if he would use GEDMatch and he was like, ‘no I would never do that’, because of the Golden State Killer and how they found him. My brother said he wouldn’t want to be responsible if anything happened to a family member because of him. Little did I know that I would soon be in that situation.”

Fast forward a few months and Jennings received a slew of Facebook requests that said: “Are you related to Jerry [Lynn] Burns in Iowa?”

“They told me my name was part of a search warrant … that this guy had killed a girl 40 years ago and they had just found him from the DNA I had uploaded to GEDMatch.”

The people who contacted Jennings on social media were connected to Michelle Martinko, who was 18 years old when she was stabbed to death in a carpark in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in December 1979. After the genealogical data from Jennings was secured, investigators covertly obtained a straw used by Burns, which then matched DNA found on Martinko’s dress.

“One girl had gone to school with her and had very similar looks to her and I think felt it could have been her. Her family and friends had been following the case all this time, for 40 years. Some had even done some investigating themselves. They had been constantly reminded of it,” Jennings says.

“I love reading true crime stories and I was now part of a true crime story myself. But at the same time, I was hoping nobody was coming after me, and that nobody was mad at me from his side of the family. I had never met him or any of them.”

Technically, Jennings, 41, and Burns, now aged 66, are “second cousins once removed”.

“We have the same great grandparents,” she says.

“Never once did the police contact me. I never would have known if it wasn’t for these people on Facebook who contacted me about it.”

Burns’ conviction did not change the stance of her concerned relatives.

“My brother maintained the same position. He did think that if you commit a crime [like Burns] you need to do your time, just like anybody else, but he wouldn’t want to be the reason they got caught,” Jennings says.

“My other brother, I got him signed up to it, and I am still on there, but my sister took her name off GEDMatch.

“I am really sad that [Martinko’s] parents had passed away before they found out who it was. They went to the grave [incorrectly] thinking it was her ex-boyfriend, so that’s very sad, but her sister is still alive, and she got some closure on it at least.

“The best part with genealogy data is even just a partial match will work [compared to police DNA databases which require exact matches]. It really is a breakthrough. I can’t even imagine how many cases that are unsolved could be solved through this, by just having a partial match.”

Finding a balance

Here is the obvious glitch with genealogical DNA: it does not just belong to you. What rights do your family members – close and distant, present and future – have if your humble swab upload unleashes unforeseen and unintended consequences?

Currently in Australia, familial DNA is used in police investigations, but genealogical material is not.

Xanthe Mallett, a criminologist and senior lecturer at the University of Newcastle, believes genealogy data should be applied “for use in cold cases like homicides and serial sex offenders”.

“It isn’t being used in Australia currently … but I’m hopeful in the future that police here will really start to look at the possibility, especially cold cases,” she tells LSJ.

Mallett works with US-based companies which set ambitious targets to solve “a cold case every week”.

“Obviously they have more cold cases and you have to factor in the scale,” she says.

“But I wish we were doing more of that here, and some of these cases could potentially be solved before they become cold cases. The use of genealogy websites is a huge avenue in this area. And in Australia we have a significant number of cases where this technology could be applied.

“I think it can bring amazing results in terms of directly investigating specific matters, such as narrowing suspect pools, gathering intelligence and that kind of thing. These will be very specific benefits when we do start using this technology more readily.”

But Mallett agrees an ethical framework should be established, as well as agreement that the crime scene DNA is only accessed by police to upload to genealogy websites.

“You’ve got to remember that when you load your data to a genealogy website, you’re actually uploading your entire family,” she says.

“It can only be done by professionals who are doing it dispassionately as part of their job, with all of that gatekeeping to make sure it is done securely. It would be an unmitigated disaster if [families or amateur detectives could access crime scene samples to try to find matches and solve cases].

“There are certainly ethical considerations around who is accessing the files and for what purpose. We do have to be very mindful of that – and one way is to ensure that this information is only used for the most serious cases; murders and repeat sexual assaults, for example.

“I think the majority of the population would accept that, because they see the outcomes; the most dangerous people being removed from the community and the benefit that solving these cases has on the victim, their family and obviously the community.

“I also wouldn’t want it to be used for a break and enter, for example. It has to have a really significant reach [of benefit to the community] before we start delving into someone’s genetic history. There are considerations around the ethics and legalities; but I am confident we can strike that balance.”

She believes that, with a threshold of serious cases established, DNA not identifiable in any police database could be tested through genealogy sites quicker.

“It could be used for contemporary investigations as well as historical,” she says.

“But we really need a unified response with every state and territory police force, and any analysis of genetic material needs to be done working across borders, given we know offenders often move between them, and it has to be shared at a national level.”

[This kind of data] can identify people who really don’t want to be known for all sorts of reasons. There is so much you can find out about unique identifying data and it doesn’t just apply to the present: this can have consequences several generations on.

Xanthe Mallett

The Golden State Killer

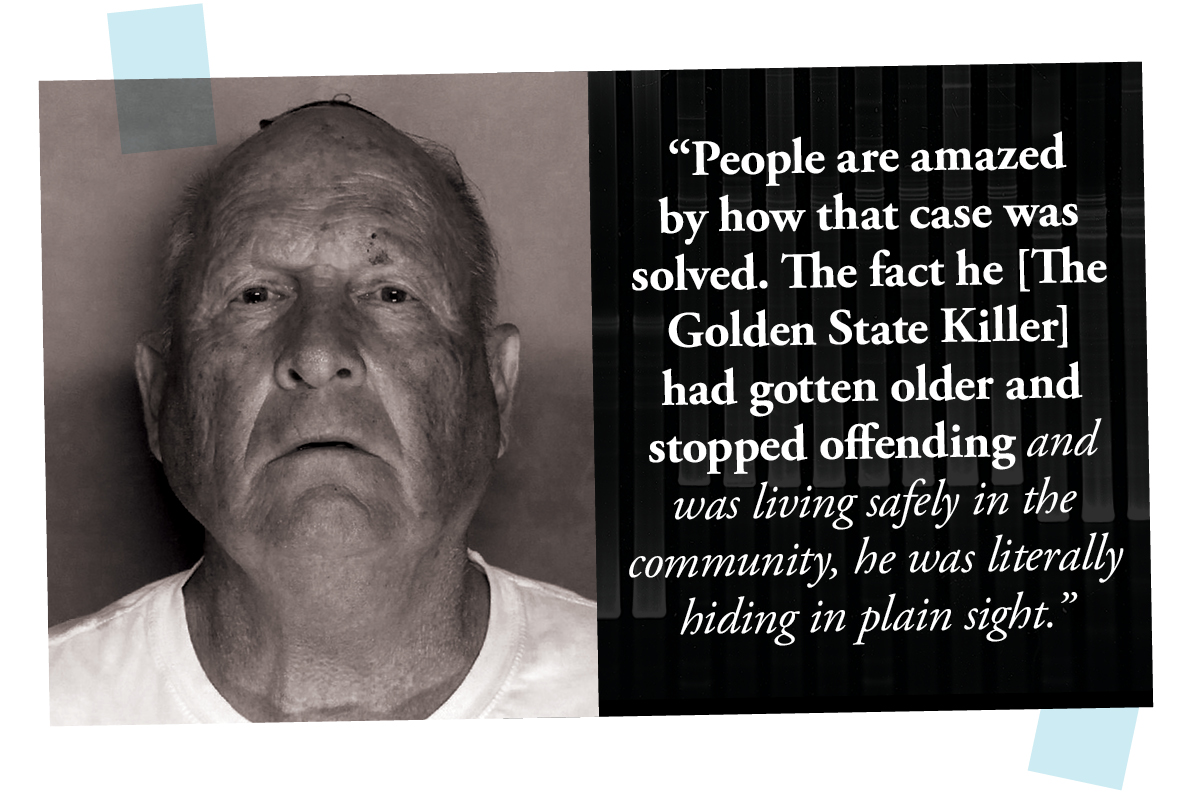

Last year, former police officer Joseph James DeAngelo pleaded guilty to 13 counts of murder and 13 counts of kidnapping between 1973 and 1986. He also admitted to several offences of rape and burglary, but the statute of limitations in California had passed. Despite extensive police searches for the murderer, later dubbed the Golden State Killer, over the ensuing decades following the attacks, DeAngelo never came to the attention of authorities.

That is, until genealogist Dr Barbara Rae-Venter uploaded a crime scene sample to GEDmatch, the same website used by Brandy Jennings and more than 1.3 million other curious Americans.

Following the Golden State Killer success, genealogists assisted US Police with identifying suspects in dozens of other cases. A month after the first conviction in June 2018, the first exoneration through using genealogical material from a public website was recorded.

“People are amazed by how that case was solved. The fact he had gotten older and stopped offending and was living safely in the community, he was literally hiding in plain sight. The amount of victims he left, and traumatised families, I think that was such a remarkable case and solved in a very innovative way. People’s minds were blown as to what is possible now,” Mallet tells LSJ.

DeAngelo’s DNA was a match with a family tree of distant relatives, whose profiles had been added to the site previously. But no sooner were the handcuffs on him than questions emerged about the ethics of using such technology to attempt to solve crimes. Among the concerns were the absence of any formal regulation or oversight process for uploading data and extracting suspects.

To protect or to prosecute?

With unexplored possibility comes risk. Dr Allan McCay and Dr Christopher Lean from the University of Sydney are researching the possible consequences of genetic profiles being used by the courts to infer information about offenders prior to sentencing.

The pair tells LSJ this material “isn’t just evidence of who they are, at least in some jurisdictions around the world it might be [used as] evidence of what sort of person they are”.

“As an example, the prosecutor may wish to show that an offender is dangerous or impulsive, and genetic data could be argued to be relevant to sentencing,” McCay says.

“There is research that suggests males with a low-activity monoamine oxidase A gene (MAOA), who experience maltreatment when young, are significantly more likely to be impulsive and aggressive compared with the general population.

“And if genetic data inferred from an offender’s relatives in a public database, like these websites, suggests they have low-activity MAOA, and there is evidence about the offender’s adverse childhood, it might be argued in sentencing that this presents an increased risk of future violence, even if an offender did not contribute to the database by providing a sample themselves or was unwilling to participate in genetic testing. And that could be used to argue for a longer sentence.

“This is pretty disconcerting, and it is probably not something that would cross people’s minds when they decide to join one of these websites.

“It is important to consider the legal possibilities and also the complexity and contested field of behavioural genetics, including how genes interact with environmental factors.”

Lean adds that the profiles uploaded publicly now also mark the DNA “of future generations to come”.

“We may feel it is innocuous now, the way it is being currently used, but it does create all sorts of new ways in which it can be possibly manipulated,” he says.

Opening (and closing) the floodgates

In the wake of the Golden State Killer arrest and ensuing furore over privacy, GEDMatch introduced an ‘opt out’ button on their site if users do not want their genetic material shared with law enforcement.

Lean says the flimsiness of privacy protections, and how easily they can be penetrated, remains a live issue. Some genealogy websites attempted to place restrictions on the use and extracting of data, but technology experts quickly showed how the privacy safeguards are easily exploited.

“Conditions need to be made solid for the use of this kind of data … our current situation in Australia is extremely piecemeal. There are few legal protections compared to Europe, America and New Zealand [where frameworks are in place],” Lean says.

“It can identify people who really don’t want to be known for all sorts of reasons. There is so much you can find out through this unique identifying data and it doesn’t just apply to the present: this can have consequences several generations on.

“Having this trend of gaining information about people through their genetics and building profiles … God knows how we are going to use it in the future. I am mainly worried that we are creating all these different tools that can be used in so many different ways and we really need to think about regulatory frameworks to steer the use, making sure they are being constrained to being used in the most ethical way possible.”

Mallett says she is “personally comfortable” with her DNA being on such databases.

“If I could help lead to somebody being identified or arrested, I would be happy. We just have to make sure we do it in the right way,” she says.

In August 2020, Jerry Burns was sentenced to life in prison; and more than two years on from that flurry of Facebook messages, Jennings hopes more people elect to upload.

“I really wish that more people would sign up or choose the [opt-in] option on GEDMatch. This pot of gold is limited now by people not choosing that option, and I would encourage anyone who has opted out of it to opt into it, because of the good that can come from it. In my case, it was closure for these people after 40 years. What can be better than that?” she says.

“I really feel if you don’t have anything to hide there’s not really much risk in doing it. I think the good outweighs any bad that could come out of it.”