A lot of people don’t have a proper understanding about consent, because many grew up in the era of ‘no means no’.

Sexual assault and consent law have dominated the national conversation over the past 12 months. State governments remain at loggerheads over differing definitions of consent, as calls for societal change grow louder. But while new legislative reforms in NSW hope to change the experience of survivors in the criminal justice system, Keely McDonough reports community attitudes have a long way to go in keeping up.

WARNING: This article discusses sexual assault. LSJ advises you discontinue reading if this topic is triggering for you. Contact 1800 RESPECT, or the Solicitor Outreach Service (SOS on 1800 592 296) for confidential counselling if you are a NSW solicitor. Always dial 000 in emergencies.

It’s not long into a conversation about sexual assault and consent law that criminal defence lawyer Trudie Cameron gets right to the heart of the issue.

“I recently told someone: next time he’s sitting in the pub with a mate who says, ‘oh that girl looks really hot, I might see if she wants to go home with me’ – and if he thinks that girl is too intoxicated to consent – he should be telling his mate that rather than putting her in a cab and taking her home [with him], he should be putting her in a cab to her own house,” Cameron tells LSJ from her office at Armstrong Legal in Sydney.

Cameron is a criminal lawyer with more than seven years’ experience acting for clients charged with offences ranging from drink driving or minor drug possession to murder or manslaughter, a “decent chunk” of which are charged with sexual offences. The lack of education and awareness, Cameron says, is a major problem across society when it comes to consent and sexual offences.

The NSW Government passed affirmative consent laws in November, following ongoing advocacy by victim-survivors and an extensive review by the NSW Law Reform Commission. The reforms have been hailed as a significant milestone in the fight against perpetrators of sexual crimes.

But like Trudie Cameron, NSW Attorney General Mark Speakman agrees there is a long way to go to tackle “lagging” community attitudes.

“Particularly in the 16-24 male cohort, there is a lack of understanding about what consent is, how you talk about it, how you ensure that it’s present and that it’s understood when you’re having sexual intercourse,” Speakman tells LSJ.

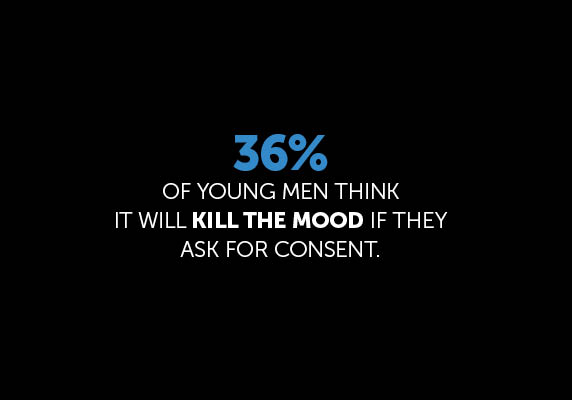

“Some of the research we’ve done suggests consent is rarely discussed among young people, and about 38 per cent of young men think it will kill the mood if they ask for consent.”

Requiring an “enthusiastic yes” for consent is the goal of the legislative reforms, which now stipulate consent to any sexual activity must be communicated by words or actions, not simply assumed.

The affirmative model, which will commence in May 2022, is expected to make sexual assault cases easier to prosecute. The laws intend to address “grey areas” around an accused’s belief the other person was consenting. Previously, cases where a victim had a “freeze response” (a common physiological reaction to danger or fear) had not always resulted in convictions.

“If I’ve got a client in for a completely unrelated offence, I may have a conversation with them [about consent] because quite frankly I don’t want them to come back and be my client again,” Cameron says.

It’s an issue so close to her heart, she volunteers her time to give presentations to high school students about consent and sexual offences.

Trudie Cameron, Criminal Defence Lawyer

Trudie Cameron, Criminal Defence Lawyer

While the reforms are a positive step forward, Cameron argues legislation alone will not fix the broader social misunderstandings, and it needs to be coupled with widespread education and awareness campaigns.

“Your average man in his 20s, 30s 40s, 50s, is not going to read the bill. They’re not going to hear the second reading speech, and they’re definitely not going to understand the text of the legislation and what that means when they find themselves in a bed with a partner,” Cameron says.

“A lot of people don’t have a proper understanding about consent, because many grew up in the era of ‘no means no’. ‘No means no’ implies consent is only absent where a person is told ‘no’, which is not the case.”

Calls for change

The conversation about sexual assault has grown dramatically louder in recent years. It began in early 2021, with the allegation from former Liberal staffer Brittany Higgins that she was raped in Parliament House. Waves of accusations out of Canberra followed. Discontent manifested into marches across the country as thousands of people, mostly women, shared their stories.

Commander of the NSW Police Child Abuse and Sex Crimes Squad, Detective Superintendent Jayne Doherty, says this heightened media attention around consent and workplace behaviour encouraged more victims to come forward.

Data by the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) confirms this, revealing sexual assault offences in NSW increased by 21 per cent in the 24 months to June 2021.

“A lot of people then started to say, ‘well hang on I’ve had this incident where I was intoxicated and didn’t come forward, but now maybe I’ll be supported so I will come forward’,” Doherty tells LSJ.

“When you see the month-on-month statistics, if you compare that to when there was a big thing in the media over sexual violence, we tend to get more reports. We can only guess from that how many unreported ones there are… it could be one or it could be a million.”

The temperature is still rising and survivor advocates like Saxon Mullins and 2021 Australian of the Year Grace Tame are cranking up the heat on governments to lead change.

Mullins, the complainant in the highly publicised and controversial rape trial of Luke Lazarus, was a key figure in contributing to the passage of the new affirmative consent reforms, tirelessly advocating for victims. ABC’s Four Corners program aired Mullins’ story in May 2018, prompting Attorney General Mark Speakman to request the NSW Law Reform Commission conduct a review of sexual consent laws.

Mullins maintained she “froze” in fear during the assault behind a Kings Cross nightclub in 2013, but Lazarus gave evidence that her silence, indicated her consent.

The judge overseeing the case, District Court Judge Robyn Tupman, famously said in her judgement: “Whether or not she consented is but one matter. Whether or not the accused knew that she was not consenting is another.”

The new reforms now put the onus on both individuals to say or do something to communicate consent. Where the issue is whether or not an accused person had reasonable grounds to believe the complainant was consenting (as opposed to actual knowledge of an absence of consent or recklessness as to consent), an accused persons “belief” will not be reasonable unless they took affirmative action to confirm there was consent.

While Defence Lawyer Cameron agrees this will likely secure more convictions, she foresees complications in the way they will work in practice.

“I’m not suggesting the legislative reforms are necessarily a bad idea. I’m not suggesting the reforms themselves shouldn’t have been passed or there is an inherent problem with them, what I am suggesting is it undermines an accused persons right to silence and in practice it will mean they will need to produce positive evidence about this affirmation,” Cameron tells LSJ.

Concerns were also raised in the Law Society of NSW’s submission on the draft proposal of the new laws, suggesting the amendments were “unnecessarily complex” and the focus should instead be on “mitigating the stress and trauma of the trial processes on complainants”.

But Speakman says this shift will ultimately improve the experience of complainants in the criminal justice system: “The conviction rate probably will go up, but that’s not the primary focus of this, and it’s certainly not the intention to have unfair convictions.”

The reforms will also enshrine in legislation five new jury directions to address societal “rape myths”, such as false ideas that sexual assault is a crime perpetrated by violent strangers, unknown to the complainant. Juries will be explicitly reminded sexual assault can occur between acquaintances and people who are married or in a relationship, that it is not always accompanied by violence or physical injury, and there is no “normal” response to being sexual assaulted. It’s the first-time specific directions are being given for an offence in NSW.

“It’s a good thing because consistency is something that will only improve the way in which criminal trials run through our criminal justice system,” Cameron says.

“They’re directions that already exist but now they are targeted at addressing some common societal misunderstandings about consent and how it operates.”

Commander Doherty says the directions will hopefully address the misconception within society that sexual assaults are always violent rapes. “If someone has injuries or the circumstances around it are quite violent, juries have no issue with finding that it is without consent. But when we have a lack of those things, that’s when juries struggle to find beyond reasonable doubt.”

Changing societal attitudes

Almost 2 million Australian adults have experienced at least one sexual assault since the age of 15, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ 2016 Personal Safety Survey. It’s the equivalent of one in six women and one in 25 men.

“There will always be sexual offending, there will always be people who commit horrible dreadful sexual offences, but there are ordinary people who come before the courts where there’s been a miscommunication about consent … or there are two parties who have completely different versions about what happened … The way to change that, is to increase education [about consent],” Cameron says.

The NSW Government has recently conducted focus groups and questionnaires to, as Speakman tells LSJ, “work out what buttons we need to press”.

“We are doing market research to test attitudes and we have found some disturbing attitudes for young men, in between 16 and 24,” Speakman says.

“In our survey, about 14 per cent of them didn’t agree that you must seek consent every time you engage in sexual activity. When unprompted, only 22 per cent of young men identified asking as an aspect of consent. There were 12 per cent of young men who didn’t agree with the proposition that a person can’t consent if they’re asleep, passed out or unconscious.”

These “backward and archaic” views are echoed by the most recent National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS), funded by the Department of Social Services.

The survey found of Australians aged 16 and over, 42 per cent agreed it was “common for sexual assault accusations to be used as a way of getting back at men”. Further, 33 per cent believed “rape resulted from men not being able to control their need for sex”.

Detective Superintendent Jayne Doherty, Commander of the NSW Police Child Abuse and Sex Crimes Squad

Detective Superintendent Jayne Doherty, Commander of the NSW Police Child Abuse and Sex Crimes Squad

I think there is still a lot more room to bring court up to date with victims and make it a victim-centric experience …We are a justice system, allegedly, but sometimes you wonder where the justice lies.

Alongside the reforms, the Government is using this data to develop a new targeted education and training program for both participants in the criminal justice system and the wider community. Part of this will be rolling out another phase of their successful #makenodoubt campaign, initially launched in late 2018.

“We are looking at social media that will hit the spot with short messages that will appeal to young men. It’s a positive, not a punitive message that will be more effective than a huff and puff lecturing style,” Speakman says.

Consent is included in the NSW curriculum for both public and private schools, but Commander Doherty says education and training needs to be funnelled through all levels of society.

“If we start with the young ones and bring it through generationally, that’s where we need to aim,” Doherty says.

“We are already doing presentations to certain targeted groups like football clubs and sporting groups. Workplaces and big businesses need to start pushing this too. We do it with domestic violence, but everyone shies away when you say the word sex.

“Men are victims too and we need to recognise that. It’s not just a women problem, it’s a whole society problem. Male champions will help get that across.”

Victim-centric approach

The justice system is at the forefront of tackling, managing and preventing sexual assault, but there are complex barriers to reporting; a lack of trust in police is one of them.

The 2020 report into sexual assault by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found in almost 9 in 10 incidents, women who experienced their most recent aggravated sexual assault by a male in the last 10 years did not contact the police.

Commander Doherty has been at the helm of the NSW Police Child Abuse and Sex Crimes Squad for less than a year but is pushing for sweeping change to police culture, overhauling the way police are trained, react and present for victims.

“We measure on our legislative outcomes – was someone charged, were they convicted. What we are looking at is our measurable, being how we supported the victim. If the best way we can support that victim is by taking their story, having someone believe them and giving them access to services, then that’s what we will do,” Doherty tells LSJ.

“It’s all about supporting people along the way. For a lot of victims, it’s not a court outcome they want, but where else do you go when you’ve been sexually assaulted?”

Under a new sexual violence framework for NSW Police, police stations will become more inviting and conducive for victims to tell their intimate stories. The pathways to reporting will also be revamped, including bespoke change to the Sexual Assault Reporting Option (SARO) online form that is currently in place. The NSW Government is also undertaking a major research project with BOCSAR, looking at the experience of complainants from the moment they report right though to sentencing.

“We know there appear to be many obstacles to complainants going through with the whole process, and that could include the way they are treated at a police station, how their complaints are handled by police, their experience in court and the low conviction rate could be a disincentive,” Speakman says.

In the case of Luke Lazarus, Saxon Mullins as the complainant went through a four-year painstaking legal battle, two trials and two appeals just to see the original conviction overturned.

“When you think of a victim in court who had a traumatic thing happen to them. And then they have to relive that by telling the police, counsellors, and then sitting in front of a court, in front of a magistrate, in front of a jury, once, twice, three times. We’re adding more and more trauma to the victim,” Doherty says.

“I think there is still a lot more room to bring court up to date with victims and make it a victim-centric experience …We are a justice system, allegedly, but sometimes you wonder where the justice lies.”

The sticking point that Speakman, Doherty and Cameron all agree on is that legislative change is only one part of the puzzle; societal attitudes will change by educating and informing.

“We had Jarryd Hayne’s victim walk out of court and get spat on, what does that tell you about our society? That we would support someone because they are a good football player against a girl who came forward and told her story pretty consistently a number of times,” Doherty says.

“Whether that’s juries, barristers, solicitors or judges; everyone in the court system needs to have that same understanding and be supportive. That way we come to the truth.”