Just Reinvest NSW formed an idea for the ‘Australianisation’ of justice reinvestment, particularly with a view to addressing the over-representation of Aboriginal people in prison and particularly Aboriginal children and young people.

Justice reinvestment offers a rational, long-term solution to curb soaring costs in the NSW criminal justice system.

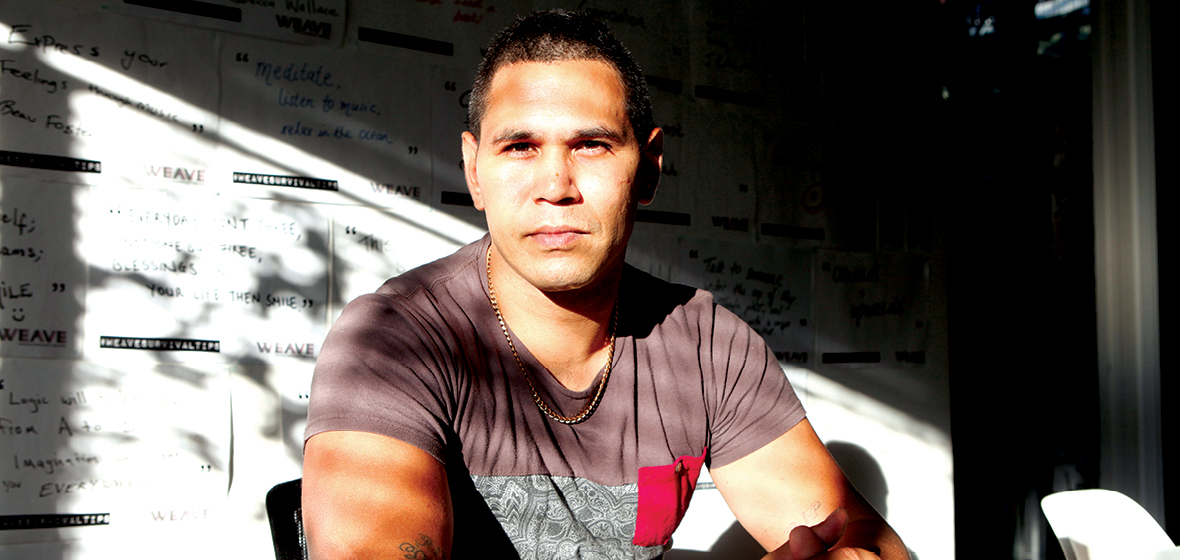

Ten years ago, if teenager Keenan Mundine had made a bet that he would not make it out of the NSW prison system, it would have been a wager with reasonable odds. According to the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR), as an Indigenous child, Mundine was 24 times more likely to be incarcerated than his non-Indigenous peers.

The NSW Aboriginal Legal Service says that he would have had a 55 per cent chance of returning to prison within two years once released as an adult. An orphan from the age of eight, Mundine was also like one in three people released from prison – he spent his first night out of prison sleeping rough, matching research by the Public Interest Advocacy Centre.

“I didn’t have a place to stay, I didn’t even have shoes to put on my feet,” Mundine recalls.

“I’d get out [of detention] and two or three of my friends might still be locked up, but there’d be others on the outside. We would steal, sell drugs and do what we needed to survive. Then maybe I’d be locked up again and others would get out. That was our life.”

Mundine was 14 when he began the cycle of offending and reoffending that consumes the life of many ex-inmates. It was a standard Friday night in his neighbourhood on The Block in Redfern, when police caught him at 2am breaking into a car to steal a laptop. A cold, 40-minute paddy wagon ride later, and Mundine was squinting up at razor wire under the fluorescent lights of Reiby Juvenile Justice Centre in south-western Sydney.

Other 14-year-olds might have cried when they were told to drop their pants for the mandatory strip search, but this teen was nonchalant.

“It was sort of a logical step in my journey,” Mundine says. “Everyone who I was hanging around had been to prison already. To me and most of my friends, it was a rite of passage.”

Mundine, now 29, spent 10 of his birthdays in a prison cell. He is one of many prisoners who become institutionalised at a young age and, once released, return to the same socio-economic circumstances, burdened by the stigma and employment challenges that come with a criminal record. The prison system often is referred to as a “revolving door” because the cycle of reoffending can be so difficult to escape.

“We really shouldn’t be surprised that so many [ex-inmates] go back into custody,” says Sarah Hopkins, Chair of Just Reinvest NSW and Managing Solicitor of Justice Projects at Aboriginal Legal Service (NSW/ACT).

“According to BOCSAR, the average prison sentence in NSW is 10 months. You are taken out of your community and because your sentence is short, you have little or no access to pre- and post-release programs. Then you are just dumped back into the community, so you have the exact same problems as those that sent you in there in the first place.”

Hopkins is a solicitor who has represented Indigenous offenders at the Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT for 18 years and says she has witnessed the destructive effects of incarceration on young people throughout her career. By 2012, she became convinced there were better ways to spend money in the justice system and, along with a small group of like-minded supporters, helped to form Just Reinvest NSW.

Since then, the independent, non-profit association has engaged the support of more than 20 organisations, with additional individuals providing in-kind or volunteer support to lobby for a new approach to NSW criminal justice.

The Just Reinvest campaign comes as imprisonment rates in NSW are skyrocketing: BOCSAR statistics show that the NSW adult prison population grew by 15 per cent in the past two years, and is now at a record high of about 12,500 – up 17 per cent since last year.

An alarming report by the independent NSW Inspector of Custodial Service released in March reported that some jails had put mattresses on the floor so three prisoners could fit in one-person cells to cope with over-crowding.

The report said self-harm in prison had increased by more than 10 per cent in the previous two years and that a lack of communal space meant some prisoners stayed locked in their cells for up to 21 hours a day.

Apart from the emotional cost to families, communities and young offenders churning through the revolving door, the prison system is costing NSW billions of dollars. In June the NSW government budgeted a record $3.8 billion investment in the state’s prison system to cope with the surging population. Just Reinvest says it costs an average $290 per day to keep each adult prisoner on the inside. For children in the juvenile system, it is $652 per child, per day, or $237,000 a year. Based on the 2015 Profile of the Solicitors of New South Wales report by Urbis, in which the average annual salary of a solicitor in NSW was $116,000, we are housing juvenile prisoners at a cost more than double the average salary of a NSW lawyer.

The name Just Reinvest comes from justice reinvestment, an idea that originated in the US when Texan prison populations were beyond capacity after a 300 per cent increase in prisoner numbers between 1985 and 2005.

In 2007, Texas had planned to spend $500 million on new prisons but chose instead to reinvest that money into prevention programs for low-level, non-violent crimes. According to a 2014 report by the US Bureau of Justice Assistance, this ground-breaking approach saved $210.5 million in prison costs in two years, and billions in projected costs by curbing the growth of prisoner populations.

“Texas is always the example that is thrown out there because it has such massive numbers and the cost savings were enormous,” Hopkins says. “In Australia, we are looking at a different level of savings and reinvestment, but that’s not to say it’s not scalable.

“Just Reinvest NSW looked at the work of the former social justice commissioner Tom Calma and formed an idea for the ‘Australianisation’ of justice reinvestment, particularly with a view to addressing the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people in prison and particularly Aboriginal children and young people. The distinction with the US is that we saw it as an opportunity for a community-driven approach that builds the capacity of Aboriginal communities to drive their own change.”

SARAH HOPKINS, Chair, Just Reinvest NSW.

SARAH HOPKINS, Chair, Just Reinvest NSW.

In 2014, Hopkins led Australia’s first justice reinvestment trial in the community of Bourke in northwest NSW – a project that won the 2015 National Rural Law and Justice Award.

Hopkins and her team found that nine in 10 Indigenous 10-17 year olds in Bourke would reoffend within 12 months of leaving prison and that six in 10 were being sent back to prison.

“A lot of these kids were not attending school, and hadn’t attended school for a long time,” says Hopkins. “It could be that mum was in jail or dad was in jail. It could be due to drug and alcohol problems in the family. It could be that there was some level of abuse within the household. There was a high level of social disadvantage – an extremely high level of social disadvantage in many cases. Young people saw the prison system as an inevitability.”

Hopkins and her team analysed corrections statistics for the region and found that a substantial number of the offences that were landing young people in prison in Bourke were related to low-level crimes. A young person would miss curfew and breach their bail conditions – then be sent to jail, for example. Others who didn’t have easy access to a Roads and Maritime Authority centre or parents to teach them would be caught driving without a licence. If caught on multiple occasions, they’d go to jail. “There’s no public transport in Bourke and, without a licence, people often can’t get a job or go to work,” says Hopkins. “So we set up a driver licensing program to help young people to obtain their driver licence and, hopefully, avoid unnecessary arrests and jail.”

Another new “circuit breaker” set up as part of the project is the Bourke Warrant Clinic, which has established a support team for young people including workers from Youth Off The Streets, the Department of Family and Community Services as well as education and health officials. When a warrant is issued for the arrest of a young person, the Aboriginal Legal Service can request that the magistrate holds the warrant for two weeks so that the young person can prepare a plan to address their offending, such as by attending school or a mental health facility, or helping to build community infrastructure.

“It’s so easy to paint all this as a soft on crime approach, but it’s the opposite of that,” says Hopkins. “It’s thinking, ‘How can we be hard on crime by preventing it happening in the first place?’ This is not about letting violent or dangerous offenders out of prison. Some people need to be separated from society because they’re putting society at risk – no one is arguing with that. But what we also know is that many people are in prison and really shouldn’t be there.”

Since 2013, Jill Guthrie, a researcher from the Australian National University has been conducting a justice reinvestment research project in Cowra, funded by the Australian Research Council. Guthrie’s research concluded that implementing prevention programs to target low-level crimes such as breach of fines, breach of court proceedings, non-violent property theft and drug and alcohol abuse would save Cowra’s State electorate of Cootamundra $23 million in just 10 years.

“That means there is notionally $2.3 million a year being spent on what the community considers ‘justice reinvestment-amenable’ crimes,” says Guthrie. “This money could be reinvested into the community to fund further projects such as a homework centre for children, a halfway house for returning prisoners, drug and alcohol services and mental health treatment centres.”

After seeing the astounding results of Guthrie’s research, Katrina Hodgkinson, the Cootamundra State Member of Parliament, raised justice reinvestment in a notice of motion in NSW Parliament on 10 May. Hodgkinson has asked the Attorney-General, Gabrielle Upton, to invest part of the $2.3 million that could notionally be saved each year, into a justice reinvestment pilot program for Cowra. The Attorney-General’s Department and Corrective Services NSW (CSNSW) refused to answer the LSJ’s specific questions about whether the idea could become part of criminal justice policy in NSW.

“The Department of Justice is reviewing the effectiveness of measures regarding imprisonment and rehabilitation in line with the Government’s target of reducing reoffending by 5 per cent by 2019,” a CSNSW spokesperson said.

In March, the Australian Red Cross’ Vulnerability Report called for State and Federal governments to “rethink justice” and start trialling justice reinvestment in communities nationwide. In the report’s foreword, the Public Interest Advocacy Centre and former High Court Justice the Hon Michael Kirby voice their support for the idea. Kirby notes the overrepresentation of Indigenous offenders in prison as a “special source of shame for observers of the Australian prison system”.

“The time is right for a more rational, economic and humane approach to our national ways and our trend of incarceration,” Kirby writes.

Mundine says it was a rational and humane approach that offered him a chance to break out of his prison spiral. In 2013, he committed a robbery while high on methamphetamine – a drug he first tried when he was in prison at 24 – and requested that he attend a drug treatment program as an alternative to jail. The judge agreed to the treatment program and Mundine elected to attend Weave Youth and Community Services as part of his treatment program.

Weave Youth & Community Services is a not-for profit community organisation that has been working with young people, women, children and families in Sydney for 40 years. Weave’s vision is to build a strong, connected community with opportunities and justice for all. Weave offers a range of programs including casework and counselling, support for mental health and alcohol and drug issues, domestic violence and homelessness.

According to its 2012-2013 annual report, Weave receives half of its $2.265 million budget from the NSW Government, 31 per cent from the Federal Government, and the rest from grants, donations and fundraising.

Since attending Weave, Mundine has developed a relationship with a long-term family friend, Carly. They are now engaged. Inspired by his life experiences and passion for change, Keenan enrolled in TAFE to study youth work, and after a year attending Weave, he was offered his first paid job as a youth worker. On his first day of work, he found out that he and Carly were expecting a baby.

Mundine is an ambassador for Just Reinvest NSW and says he wants to shift the focus from imprisonment to diversion and pre- and post-release support to tackle the over-representation of Aboriginal people in custody. He doubts the value of spending billions on new prisons and extra beds, as forecast in the 2016-2017 NSW government budget for $3.8 billion to be invested in the state prison system.

“I want Weave to be a first stop for young people needing support,” Mundine says. “Let’s take money out of the planned new detention centres and create community-based programs that can address these issues. I want to share my story and show the people who are going through the same things that I went through – there is hope. You can make it out of the system.”

Keenan Mundine tells the real story of life in and out of prison“I was born in the ‘80s and I grew up on The Block in Redfern in the early ‘90s. At that time, Redfern wasn’t really a great place for children. Heavy alcohol and drug use was out in the open. Alcohol, weed, heroin, cocaine … it was just rife. Heroin had just been introduced to my community and I watched people from a young age succumb to the effects. Empty homes were used as drug dens. There were people shooting up, outside my house, in the backyard, in the laneway, in the school. Overdosing, violence, police, it was just normal to me. Then, throw into the mix that I lost my mum at seven years old. She died of a drug overdose. I was the youngest of three boys. My father was never really around and when we did see him he was usually drunk. He was an alcoholic. When my mum passed away, we stayed with mum’s brother who tried to keep us kids together. About one year later, they told us that our father was dead. He hung himself in the car park we had to walk through to get to school. At about 12 or 13 I started looking up to the wrong boys. Coming from a poor background I lacked the material things that a kid wanted and I saw these guys with the nice shoes and nice clothes and I wanted what they had. Some of them were family members, older cousins and some of them went to school with my older brothers. They said, ‘He’s alright, he’s one of us’. They became my role models. The first day I hung around them, they went out and spent $500 on me. They bought me shoes, clothes, hat, shirts, and I was like, ‘This is the life!’ Then came the eye-opener that the way they made their money involved breaking the law. With them, I started doing anything I could do to make money. I left school in Year Seven or Eight and it became my full-time job. That’s how I was taught to be a man and to look after myself. My everyday battle was, ‘Where am I going to sleep tonight? What am I going to eat?’ I was couch surfing and sleeping at friends’ and family’s places wherever I could. When I was 14, I went to prison and that began my long battle with the judicial system. I’d hang around these boys, do what I needed to do to survive, get arrested, go to a juvenile detention centre, then I’d get out and go back to the same group of boys who were still doing the same thing. Still selling drugs, breaking into houses, breaking into cars. We hung together, ate together, slept together. We got charged together, went to court together, went to the boys’ home together and got out together. Every time I got out, I had no skills, no qualifications, no support. I actually had no official identification until I was 24. A lady in the prison system helped me to obtain my birth certificate for the first time and I think she was a bit shocked when I touched it and started crying. For my whole life I had not been able to get on Centrelink until I had a Medicare card. I couldn’t get a Medicare card until I had a birth certificate and I couldn’t get a birth certificate without my parents. So I just thought, ‘F*** it. This is the system and this is my life. I’m not dead, and it can’t get much worse’. Ten years ago if you asked me where I thought I’d be now, I’d have said, ‘In jail or dead.’ I never thought that there was a life beyond that.” |