If Jake Blundell’s face evokes a flicker of recognition, there’s likely a good reason for that, even outside the career he’s forged as a legal practitioner.

As a younger man, the media-law specialist and newly minted partner at Banki Haddock Fiora traversed the landscape of Australia’s entertainment industry as a star of stage and screen. These days he’s acting on a stage that’s entirely different from that of his formative years.

Or is it?

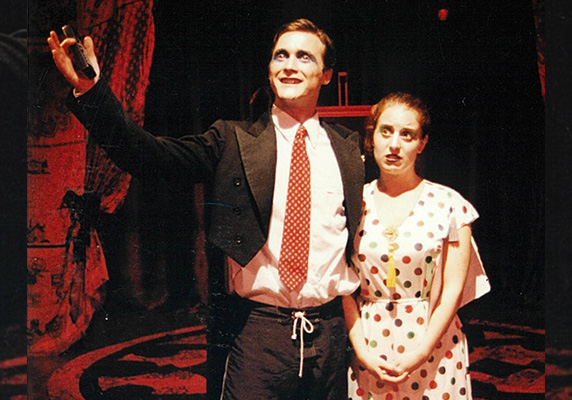

Jake Blundell has trodden the boards of some of the nation’s most celebrated theatres and appeared as an actor on screens both big and small. He’s worked as an advertising director, a photographer, a voice-over artist, a curator and gallery director and caterer, and at one point even tried his hand at the business of brewing beer. Having spent his first 30-odd years on earth taste testing from life’s smorgasbord, Jake Blundell’s path eventually led him to his spiritual home and a career in the law.

And, says the now father of two, the diversity of experiences that delivered him into the arms of the legal fraternity make him infinitely more comfortable and effective in his “real job” as a specialist in media law.

Blundell was born into a celebrated Australian entertainment family, so it was in many ways a given that the talented youngster’s formative steps would taken towards a life in the industry. His school years were punctuated by television and theatre performances, including working alongside famed Aussie entertainer Gary McDonald for a role in the 1983 film Molly the Singing Dog, a gig Blundell credits with launching his early career.

Quietly striding alongside these creative pursuits was a competing penchant for academic stimulation. As his school years drew to a close, Blundell set his sights on university, but the siren call of the screen proved strong.

“It was a bit of a dream come true to land a role in (the 1994 film) Dallas Doll with Sandra Bernhardt, so I deferred the first year of my arts degree,” says Blundell, who knew even then that he was destined to do “something else a bit more intellectually rigorous than being an actor”.

For more than a decade, and having eventually managed to tuck a Bachelor of Arts under his arm, the versatile all-rounder continued to pursue roles in the entertainment and arts industry, amassing an eclectic grab-bag of skills and experiences. That is, until, by his own admission, he realised he needed “a day job”.

“I was pushing 30 by the time I started to get frustrated with the lifestyle. It’s very difficult to earn a living [in the entertainment industry]. You’re always waiting for the phone to ring and you’re at the beck and call of somebody else. It’s very difficult to be the master of your own destiny,” Blundell reflects on his fork-in-the-road moment.

“I’d had an interest in the law earlier in my life,” he says, recalling having spent “work experience” time with family friend Ken Horler, who inhabited the entertainment world and established the famed Nimrod Theatre but was also an eminent lawyer and barrister.

“I followed him around for a couple of days, including going to the Silverwater jail to have a meeting with his client.”

The young Blundell found this “fascinating”, and recalls that the experience planted “a bit of a bug” in his mind about eventually pursuing “something to do with the law”.

“I was in my early 30s and looking down the barrel of what to do next when one of my flatmates said, ‘Why don’t you do a law degree?’ I signed up the next day.

“I absolutely loved the intellectual stimulation and I still do love that aspect of what I do. I love that you’re constantly learning.”

Highs and lows of the real world

That he learned a considerable amount while riding the rollercoaster of a life in the entertainment industry has stood Blundell in good stead for his career as a legal practitioner specialising in media law.

While some might argue the merits of calling entertainment “the real world”, there’s no doubt that having experienced the highs and lows of that sector has given Blundell an advantage in terms of the ability to empathise with clients and to appreciate the world in which they live and work.

“That’s without the shadow of doubt,” he says, acknowledging that his understanding of and experience outside the legal sector was recognised as a rare and valuable commodity.”

“Right at the beginning of my (legal) career, some of the terrific partners I worked with liked that aspect of my background and felt it added value to their offering.”

Blundell believes in the vital importance of lawyers having “some sense of what it means to be in business and needing legal advice.

“Experience in the real world and having an ability to communicate,” he says, “makes it easier to get straight to the point, which is what clients need. I think some young lawyers tend to see their advice from a legal perspective, like an intellectual game, but a client needs the short answer to the legal aspect of their problem.”

Some young lawyers tend to see their advice from a legal perspective, like an intellectual game, but a client needs the short answer to the legal aspect of their problem.

At first sight, it might seem that acting on stage and screen couldn’t be more removed from acting in court on behalf of clients, but Jake Blundell proves that’s not necessarily so. In fact, he says the former role was serendipitous preparation for the latter.

One of the most profound advantages was coming to the legal profession with proficiency in addressing a crowd, particularly a tough one.

“Most people hate public speaking, and getting up in court is public speaking. The difference is you don’t have a very receptive audience,” says Blundell in his trained dulcet tone.

“The adrenaline rush of being on stage almost becomes addictive and there’s a particular personality that’s drawn to it. It’s a similar personality type that’s drawn to the bar in the context of the legal profession. A slightly extroverted type, someone who likes to be the centre of attention,” he says, confessing that he relishes being on his feet in a courtroom situation.

“It’s exciting, just as it is being on stage – it’s a similar feeling, a similar adrenaline rush.”

Blundell believes that rush is vital to one’s performance, either on stage or in a legal setting, and quotes iconic thespian Sir Ian McKellen who once told a group of actors and other theatre folk of the nervousness he still feels before going on stage.

“He told us that the moment he doesn’t feel that fear, that sickness in the pit of his stomach, is the moment to give acting away because the thing that drives you, that rush, is missing.

“That’s how I feel when I go to court, even when I’m not appearing,” says Blundell, who was recently elevated to partner at Banki Haddock Fiora. “I think that element of uncertainty, of performance, has a touch of theatre to it. I love that aspect of it.”

The accomplished actor-turned-lawyer has also taken his love of performance to the educational stage. For a time, he was a guest lecturer for the Masters of Arts Management course at the Australian Institute of Music, offering tutelage in, among other things, the law surrounding obscenity. It’s a serendipitous interview segue, given the famous alter-ego of Blundell’s equally renowned actor father, Graeme.

Alvin Purple left 1970s middle-Australia rolling in the aisles and had outraged gentle-folk clutching their pearls at antics that were risqué if not downright smutty, even by the laissez-faire standards of the “anything goes” decade.

Blundell laughs good naturedly, admitting that his mother, herself an accomplished actor and feminist, forbade the young Jake from watching the films in which his dad played the title role.

“I didn’t see it until I was at uni at Berkely in the United States, when I hired the video from some Blockbuster somewhere in California!”

But, noting the extraordinary shift in community standards since Alvin “rode again” as a bungling innocent adrift in a sea of sexual liberation, Blundell believes such examples serve to illustrate how the law has also shifted to reflect society’s changing attitude to what’s acceptable and, importantly, what’s not.

“Community values change significantly. It’s one of the reasons defamation law has retained juries,” he says by way of example, citing the notion that sometimes judges aren’t necessarily best placed to know the prevailing zeitgeist in relation to shifting values.

“Thankfully we’ve moved in the direction that perhaps looks a bit more unkindly at Alvin Purple,” Blundell says. He adds a gentle defence of his father’s famed character: “That said, Alvin was the passive character – things happened to him rather than him being the guiding mind of the activities in those films. But can you imagine them being made today?”

Following the path of curiosity

Just as society’s principles have evolved, so too has Jake Blundell’s professional life since he told an early 1980s television interviewer that he had flirted with the idea of becoming a musician or carpenter.

“I still like the idea of being a carpenter, although my partner comments on my very soft lawyer hands now, so I don’t know if I’m still cut out for it!”

He’s happy with his career choice, and happier still that he was able to bring with him to that choice such a diverse range of life skills and experiences.

“I can still experience life through the prism of the law. I love the intellectual rigour and learning about people’s businesses and lives. This is one of the only professions where you get the opportunity to constantly open up your mind. You can follow paths of curiosity to their logical conclusions as often as you like.

“I think what makes a really good lawyer is having that knowledge, passion, interest and connection with the subject matter of what you’re doing and of your client in particular. You should have experiences in as many areas of the law as you can, but with an eye on something you feel really passionate about.”

And which area of his practice is Blundell himself most passionate about?

It’s an easy answer that comes quickly: “Being involved in the defamation reform process a couple of years ago made me realise how much I value freedom of expression and the incredibly vital part the media plays.”

While acknowledging the failings of the fourth estate – “it isn’t perfect and neither is any other aspect of our democratic society” – he is avid in his assessment of the vital role the media plays in “speaking truth to power and to uncovering wrongdoing”.

Inherent in that assessment is a comparison between mainstream and social media.

“Mainstream media, like the ABC for example, has a charter they have to comply with in all their reporting. Even in commercial media, there’s a system of ethics that apply to journalists that doesn’t apply to people on the internet,” he says, pointing to the overall trustworthiness of mainstream media as a source of information.

“It can never be perfect. That’s why we have defamation laws, to protect people’s reputations when it does go wrong. But generally speaking, it’s such an incredibly vital function that media plays in our lives.”

Pinned to the wall of his office for many years was the famed quote from English philosopher and jurist Jeremy Bentham: “Publicity is the very soul of justice” – a tenet that has underwritten Blundell’s rising legal star.

“I believe it. I also believe the idea of open justice, that justice occurs openly for all to see.”