One Fine Morning

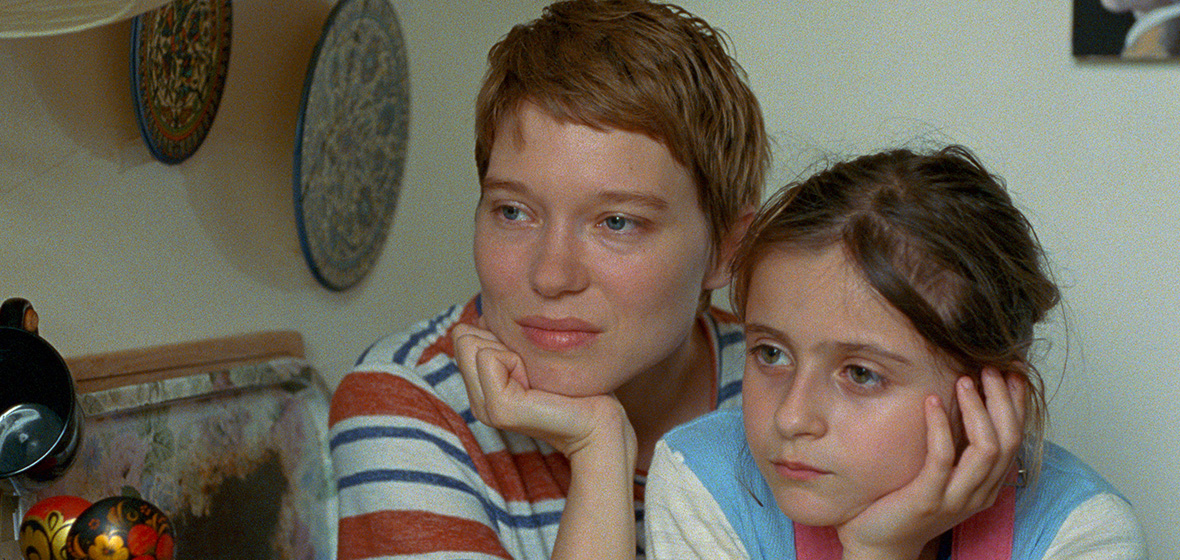

Sandra Kienzler (Léa Seydoux) is having a rough time. She’s an accomplished young interpreter living in Paris with her 8-year-old daughter Linn (Camille Leban Martins). But her father, Georg (Pascal Greggory), a well-regarded philosophy professor is suffering from a neurodegenerative disease, while at the same time Sandra finds herself in an affair with Clément (Melvil Poupaud), a married man.

In the hands of an unremarkable filmmaker, this premise is an excuse to indulge in the cryfest melodrama of obtuse emotions. The kind of filmmaker who misunderstands drama and passion with intensity and rage. This film has everything – an old man succumbing to dementia? Check. An extra-marital affair? Check. A sassy child? Check check. Sex? Of course, this is a French film. The difference, and why Mia Hansen-Løve is not an unremarkable filmmaker, is that every character refreshingly behaves like adults do.

If you know anything from Hansen-Løve’s filmography, you know what to expect. Honesty, but in a way that lets the drama come out without the need to excess. It’s effective. It enables us, the audience, to consider each of Sandra’s actions carefully.

Not every detail has to be Chekov’s gun. The fact Clément is married doesn’t mean we know what to expect for the resolution of this side of the plot. Sometimes things just are like that, and we learn to adapt. Georg’s disease is heartbreaking, but it doesn’t need to succumb to overdramatisation to make us understand the weight this leaves on Sandra. Sometimes life just deals us a bad hand, and we learn how to live with it.

None of this is dull because Hansen-Løve’s writing is natural and approachable. Each scene starts with an identifiable situation where every character reacts precisely how you think responsible people do. If there is a bit of disruptive detail, nothing is put to the test; it’s all resolved with quiet determination – which, in turn, makes it all even more heartbreaking.

The scenes with Georg are hard to watch, but Hansen-Løve’s approach is tactful. Pascal Greggory’s portrayal is caring and considerate, but the filmmaker decides not to show the worst parts of dealing with the disease. There is no exploitation; nothing like an old person shouting in despair while his daughter is confused, crying about the intensity of it all. In one of my favourite scenes, Sandra brings Georg a collection of classical music CDs and starts playing one of his favourites. He doesn’t like it, pleading for her to change it because it elicits in his memories things he doesn’t want to face. She complies, and the scene ends with us, the audience, unpacking what such a seemingly simple moment says about the grief of losing track of one’s capacities. In another moment, he tries, within his capacities, to ask her about euthanasia. It’s not a premonition, but the film addresses the theme with a heightened awareness of what this means to everyone involved, without making it the central point.

It is good to see Seydoux in a role that asks her to be more subtle. She holds her ground well. Near the end, Sandra is obviously feeling the pressure of her chaotic life while trying to keep it together for her daughter, her job, and the audience. It’s hard to play a character who cannot give in to their emotional impulses even when alone.

Hansen-Løve is often compared to Ingmar Bergman, particularly after her last film, Bergman Island, was precisely about her journey as an artist. Yet I find the Swedish director’s films patronising compared to Hansen-Løve’s observing gentlemen. For me, she’s closer to Edward Yang and Ozu, two filmmakers with a keen sense of observation, who have no intentions of shaping the world around them to their own image. Or Cassavetes, whose quiet demeanour shows so much care for his characters.

This is a soothing film. Yes, it’s sad, but so are we. It’s not an easy watch for someone dealing with dementia in their family. Georg is based on Hansen-Løve’s father (Ole Hansen-Løve, also a philosophy professor), which explains why those were the moments she decided to film – the memory of his last moments is not spoiled. And that is sad. But also so lucid, it’s almost life-affirming.

Verdict: 4 out of 5

For everyone dying to see adults in film. If you had to deal with the trauma of caring for someone with dementia, then tread carefully, but do know that this film approached it with tenderness.